The Three Feather Chief

The first example of anametric image writing I recognized.

From Bute Inlet, British Columbia, Canada (October, 1991).

From Bute Inlet, British Columbia, Canada (October, 1991).

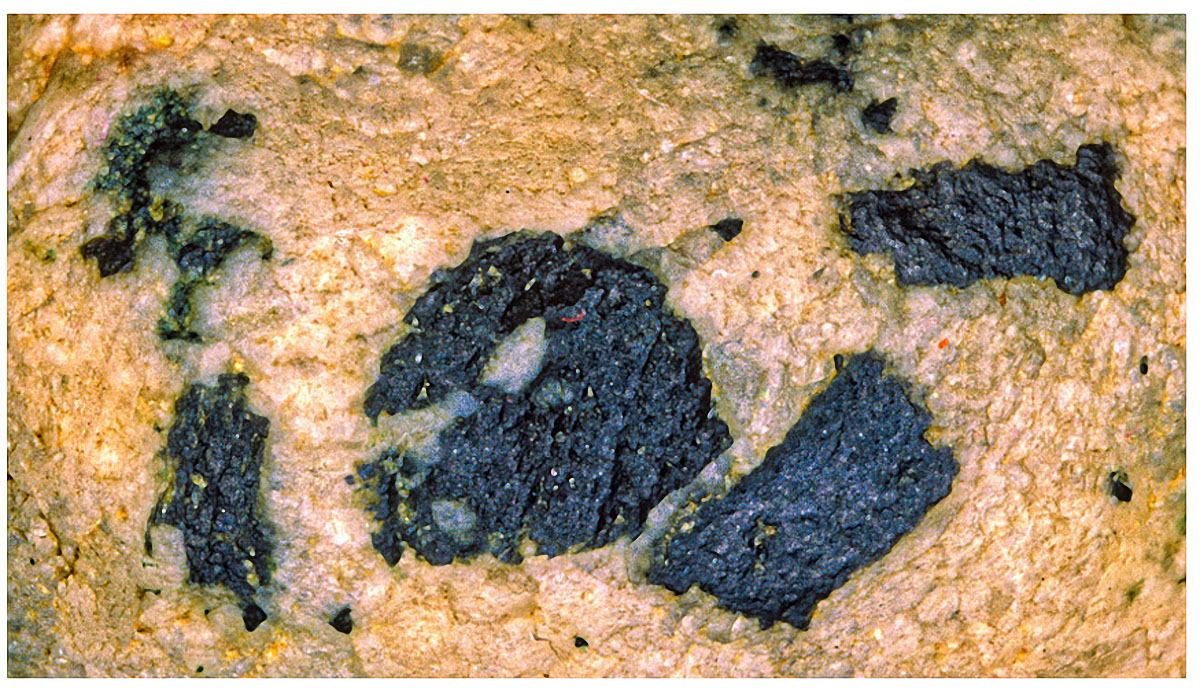

Let’s shift our attention at this point to a closer study of the distinctive constellation of marks that distinguishes the example in question. Above the eyes of the primary face, arrayed as if feathers in a headdress, there is a collection of three distinct image areas clustered together.

Looking at the image areas that compose the three feather motif, we immediately noticed that all three image areas depict tools.

The first image area or “feather” depicts a spear point and a mountain goat.

The second image area or “feather” is of a microblade core.

The third image area or “feather” presents a solid granite ax.

Despite the paucity of information available regarding the lived realities of existential situations encountered during the last ice age (an issue we may well be able to remedy, to a very great extent, through an understanding of anametric image writing), there is a solid body of information available with reference to stone tools and weapons. As noted earlier, analysis based upon the selective processing of specific spatial frequencies, taken as image areas and enabled through the application of Fast Fourier Transforms, strongly indicates a direct link between the production techniques associated with stone tool technologies, and the creation of anametric image writing examples.

Of the information which comes to us regarding the production of stone tools, some of this comes to us from studies undertaken within the archaeological record; and some is from ethnographic research, by way of interviews with people who had actually used stone tools (or remembered people who had). As with the clinical studies of non-conscious neural processes which can inform our grasp of anametric image writing, we can begin to inform the historical record created by the First Nations through their system of image writing, with the research methodologies created within the Western European academic heritage. This is an approach which is infinitely preferable to that which has been the norm — that of simply enforcing a very racist world view through rejecting anything which is not directly circumscribed and thus authorized by that Western European academic heritage, which has until now been accepted unquestionably as accurate — to the exclusion of all other bodies of knowledge.

One such study we can draw upon, Factors Influencing the Use of Stone Projectile Tips by Christopher J. Ellis, is an inclusive overview of available research on the topic of stone tools. Several pertinent observations are presented in this work, and these can assist us in orienting our own analyses. Among the points established in this paper, we find:

Stone points were used on weapons because they are more effective for killing;

Stone points were used almost without exception for large game (over 40 kg in body weight);

Spears with stone points were more effective for long distance throws than non-stone tip spears.

In summary: “The major factor indicating effectiveness of stone is its almost exclusive ethnographic association with large game. In fact, this pattern is so strong that in prehistoric cases one can almost always assume that stone points were used in large animal hunting [Ellis, pg. 63].”

This is all very useful information, and it is very helpful to us here in that the first image composite we encounter through the Three Feather motif is one of a spear point and a mountain goat. We can use the findings of this article to bolster our confidence that the spear point shown is in all probability meant to be interpreted as one made of stone. This is not an inconsequential observation, because the next two image areas in the Three Feather motif are definitively depicting tools made of stone: microblades flaked from an obsidian core, and a solid granite ax. Add to this the fact that the mouth and eyes of the Three Feather Chief’s face convey information articulated around a knife, and we begin to understand the essential role of the Three Feather Chief as a conceptual persona: that of a tool maker.

We can correlate this hypothesis with another instance of the Three Feather Chief motif, as found written in images on an entirely different stone. Here, we see the disembodied image of the Thee Feather Chief appearing to someone; and we also find numerous images that seem to depict events associated with the production of stone tools.

If we take the Three Feather Chief motif as a ‘signature’ of sorts that designates someone known for their skill in creating stone tools, then we have grounds to suspect that the diagrammatic features we are examining as image elements will also in some way present intensive ordinates in compositing conceptual structures. This will prove to be decisive for our understanding of how the grouping patterns these images compose as conceptual structures covey information.

If you look closely at the oddly rectangular spear point in the position of “First Feather” in the “Three Feather” motif, you will notice that this spear point has a series of parallel lines running the length of the point, but, offset from the axis of the point that runs to the shaft of the spear.

It was expected that this spear point would break when used; but, this spear point was designed to break in a way which left it still usable. It appears that this particular point could be broken twice, and still remain effective as a hunting weapon without the need for re-hafting a new point on the spear — an innovation that speaks to a recurring theme that always attends to the creation of stone tools: How to mitigate the breakage of tools during use, when the technologies they are produced with demand that they must be constructed from friable materials? This is a question posed, to each new apprentice in the art of making stone tools, by the materials they must use; and in that each generation might find new answers, we can see here that in a sense “the same” conceptual persona returns in attending to tool making, in a developmental spiral that stands to constantly advance technological prowess through the generations — much as anametric image writing itself evolved differently, in different geographical bioregions throughout North America. This occurs as another example of something noted earlier: a disparity in relative size that indicates the relational parameter of scale is in play. Noting that assessments of scale are informed by the non-conscious processes attributable to grid cell modules, we can gather a few other insights here: such as, that the "in between" of immanence holding across diagrammatic features seems to stabilize of a temporal dynamic associated with movement, as an event duration identifiable as an intensive ordinate.

With respect to anametric image writing itself, a different question presses at this point: how do the image elements, which compose the “Three Feather” motif as diagrammatic features, convey intensive ordinates through grouping patterns that establish conceptual structures? In answer, we can begin by assessing the first such grouping pattern, noting that the mountain goat and the spear point are shown as being approximately the same relative size. Since we know that this is not in reality the case, and that there is a disparity in size between these two in real life, we can take this proportionate disparity as being indicative of some other relational aspect inherent in the conceptual composite of this image assemblage. Such a determination allows us to shift from diagrammatic features to intensive features — that is, demonstrably intentional aspects defining relationships holding between image elements depicted. Assuming that the spear point is meant to be thrown at the mountain goat — as would seem to be indicated by their relative positions — we can intuit that the implied ratio presented indicates some manner of equality other than actual size. Given that the mountain goat will no doubt leap at some point — that’s something mountain goats characteristically do, and indeed this one is shown in the act of leaping, with its front legs raised from the ground — we would certainly have grounds to conclude that the relative size of the spear point and mountain goat, taken as contextual for the dynamics of the spear’s throw and the mountain goat’s leap, indicates the optimal moment at which to throw the spear. This moment occurs precisely as the mountain goat begins to leap, for in becoming airborne, it cannot change its speed or direction; and this is when the mountain goat will invariably land where it is headed — it can do nothing else. This is the moment when an accurate throw of the spear is most likely to hit the mountain goat — at the moment the goat is leaping into the air. If the mountain goat leaps just after, or as, the spear is thrown then the hunt may well be unsuccessful. Timing would be everything for a successful hunt to ensue.

What we have here is a fairly complex concept, recomposed from diagrammatic features through an assessment of their relative position as intensive features — a conceptual composite that is in itself an event. From the equal weighting given by size to the mountain goat and the spear point, the positional relation of both image elements, and the actual dynamics of the images depicted, we can recompose the nature of the immanence this image assemblage is meant to convey as an event. Note that, as we move from the image elements considered as diagrammatic features, through the intentionality of their proportionate relationship which marks them as intensive features, to the co-ordinated dynamics expressed here as the intensive ordinates which characterize this particular conceptual structure as a grouping pattern of image elements, we remain within a very particular context; and, it is one which we have encountered previously: that of positional localization which, as we noted with reference to the differential image elements occurring in the position of the Three Feather Chief’s eyes, characterizes the semiological nature of ‘one thing appearing in the place of another’ that demonstrates those grammatological functions which inform these image composites as a system of writing. not surprisingly, the neurological processes most directly responsible for a sense of positional localization are grid cell modules, in so far as they inform the stabilization of place cells.

At the time when this particular constellation of image elements was being composed into such grouping patterns as generate these conceptual structures, in the Near East there was barely a one-to-one ratio between trade goods and tokens being conceived, with the formalization of phonetic writing still far in the future. And yet here, we already have a differential ratio being utilized to convey a relationship between intensive ordinates that illustrates a highly refined conceptual structure —one that is directly expressive of a temporal event, rather than a simple numeric amount quantified for purposes of trade.

It is interesting to note, though, that in both cases we are dealing with the production of food resources: in the Near East, we are dealing with the production of food surpluses attributable to the development of agricultural settlements; and in North America, we are seeing the procurement of food resources contextualized to the production of those tools through which food is obtained. The development of phonetic writing in the Near East proceeded by way of units dedicated to the quantitative measurement of differences-in-degree; but in North America, we find the development of anametric image writing proceeding through temporal considerations that seek to convey differences-in-kind.

It is important to remember here that the development of anametric image writing, to such a great degree of refinement, occurred long before phonetic writing was invented in the Near East. This being the case, it is a logical absurdity to demand that such a form of image writing conform to the norms of a phonetic form of writing which did not even exist at a time when anametric image writing was already well established in North America.

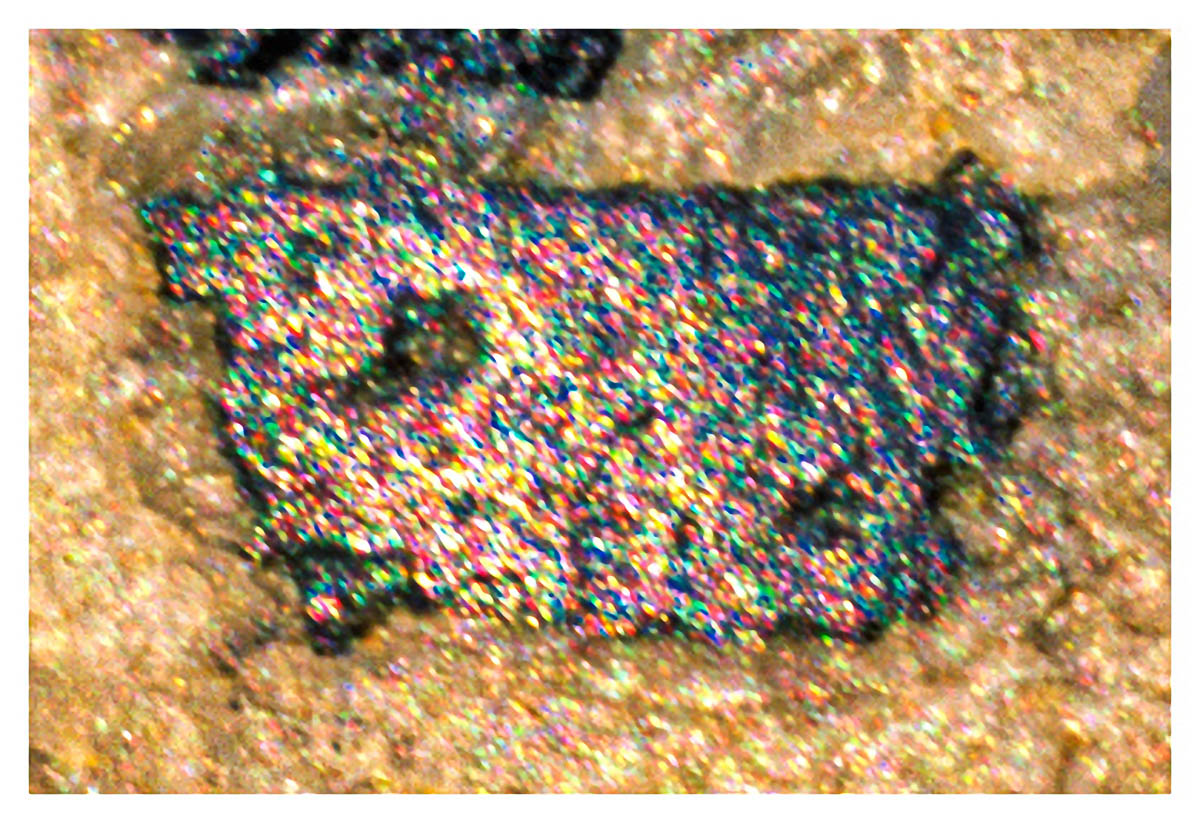

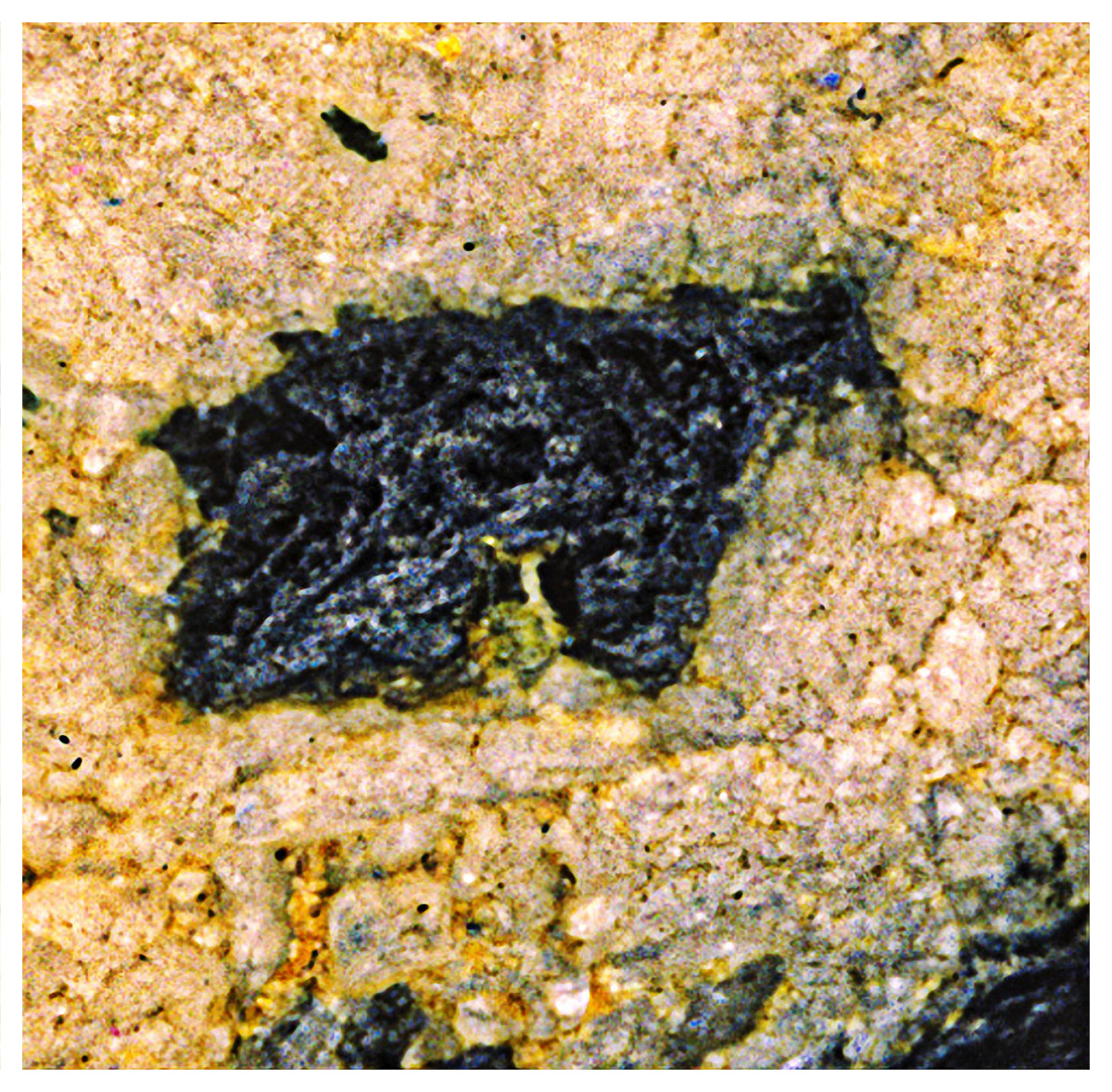

The second image area or “feather” in the Three Feather Chief motif depicts an obsidian microblade core.

In Rethinking the Origin of Microblade Technology: A Chronological and Ecological Perspective, the authors present a convincingly documented argument that microblade technology probably arose in Northern Siberia over 30,000 years ago. This date is significant, because: 1) it corresponds to the period of time just before genetic analysis indicates a separation occurred between populations in Asia and North America; and, 2) it corresponds to best estimates for the start of a developmental isolation from Asiatic cultures for the spoken languages used by the First Nations in North America. Although the exact point of origin for microblade technologies remains unclear, the authors advance evidence that a more northern location would be the most probable:

“In this paper, we argue that 1) it is logical to presume that the birth place of the microblade technology was high-latitude Siberia rather than North China, and its origin should be traced back to the early Upper Paleolithic, 2) microblade technology satisfied the technological demands of highly mobile hunter-gatherers, in particular by showing great advantages not only in hunting but also in processing resources to enable them to survive the long cold winters. These advantages consequently encouraged the spread of this technology throughout Siberia, Mongolia, the Japanese archipelago, Korean Peninsula, North China and North America during the last glacial.”

“According to chronological data and the ecological change during the last glacial, we would like to present a scenario in this way: Foragers in Siberia accumulated enough skills for microblade production with the employment of the blade technology. They adopted a higher mobility for adapting cold weather of the last glacial at high-latitude Siberia during the early Upper Paleolithic. The original microblade technology exhibited its advantages in this process, which made it rapidly spread throughout North Asia during LGM with human migration and cultural transmission. On the one hand, foragers' mobility intensified because of the harsh environment, and resulted the wide spread of microblade technology. On the other hand, the new technology was a technical support for hunter-gatherers moving more feasible in cold environment. The invention of microblade technology might be incidental: however, it is reasonable to conclude that its transmission was in virtue of the cold, harsh climate [Mingjie Yi, Xing Gao, Feng Li, Fuyou Chen: Rethinking the origin of microblade technology: A chronological and ecological perspective].”

If the occurrence of animals now long extinct gives us an upper limit in determining a point-of-origin for this North American system of image writing, the image of a microblade core in the Three Feather Chief motif at least tentatively establishes an older date, one before which it probably would not have been in use. Presumably, those animals would still have been in evidence in North America before microblade technologies came into use; so seeing both together gives us at least some sense of the historic range during which anametric image writing came into being.

Taken together, these determinations bracket the developmental history of anametric image writing quite nicely. Suddenly, several different threads connecting a variety of observations we’ve already made are being brought together, centered around microblades. We have a strong indication that microblade technology arose in Siberia over 30,000 years ago — just before the genetic split occurred between Asian and North American populations. We are told that microblade technology spread very quickly throughout northern latitudes. We see that microblade technology was particularly well suited for survival strategies during the extreme climatic conditions of the last glacial peak. We find that the raw materials for making microblades were scare (in China, at least) and difficult to obtain; and in the earliest examples of image production from North America, we also find depictions of active volcanos — the source for obsidian, a type of volcanic glass particularly well suited for the manufacture of microblades.

Let’s have a look the microblade core depicted in the Three Feather Chief motif, to see what we can learn about this technology. As noted in Rethinking the Origin of Microblade Technology: A Chronological and Ecological Perspective, and as quoted below, the peak development of this technology was a technique know as “pressure flaking”, whereby the application of pressure at the edge of a microblade core causes a small flake to detach from the core. These flakes are of uniform size, as determined by the skill of the person producing them and the uniform size of the core. A specific kind of tool is used for producing the flakes: optimally, a sharp, hard object that is easily held and which has a certain degree of resilience is ideal. The horns of animals — such as deer or, mountain goats — are perfect for this; not only due to the ease with which they can be held and the sharply defined points they bear, but also because their spring-like give allows pressure to be incrementally applied and at the same time maintained at the edge of the microblade core.

“Although the products by direct-soft-hammer are not as standard as those produced by pressure flaking, the form and size of the products are alike and can roughly serve in the same way. Since the development of lithic technology was a gradual process, direct-soft-hammer percussion might be involved in the initial stages of microblade technology, producing some less normal products between blade and microblade, and finally more pressure flaking would be applied for producing the standard microblade.

“As shown by the chronological data mentioned above, a tremendous transformation in lithic assemblages occurred in the late Pleistocene in North Asia that originated from Siberia. What was the mechanism by which microblade technology spread so rapidly and widely? Lying in high latitudes, hunter-gatherers living in Siberia faced abominable winter weather, and they adapted by developing a blade technology and later a microblade technology. Microblade technology then dispersed in Siberia and Mongolia during Last Glacial Maxima. Although there were indeed some early microlithic sites in North China, a microblade technology did not become common until Late Upper Paleolithic [Mingjie Yi, Xing Gao, Feng Li, Fuyou Chen; pg. 8].”

Looking back at the image of the mountain goat, we can note that there is a distinct separation of an adjunct image element from the area of the goat’s head where the horn would be located; and turning to the image of the microblade core, we can see an area of white detail extending from the left into the black area depicting the body of the core — a detail that is shaped as the point of a deer’s horn. We might wonder for a moment why a deer’s horn is depicted, rather than that of a mountain goat; but either would work equally well for pressure flaking microblades from an obsidian core, and the image of a deer’s horn has another important attribute: it can be presented in a way that evokes the image of a stretching, reaching, straining tip of a mammoth’s prehensile trunk (which is characteristically shown in the shape of a "C"). This coincidence of formal shape conveys not only the tool used in flaking microblades, but the degree of pressure needed (in the heaviness of the mammoth) and the inclination of the tool toward the edge of the microblade core (as seen in the attitude of the prehensile tip of the mammoth’s trunk) in order to successfully separate microblades from their core. Co-joining such disparate image elements, as diagrammatic features fused into conceptual structures, implies intensive features that yield a wealth of information in the form of event-contextualized intensive ordinates informing temporal durations diagrammatically discerned through differences-in-kind.

A microblade flake can also be clearly seen as a separate white detail upon the black microblade core; but an inverse of this is also seen to the upper right of the core, as a black microblade shown leaping from the core, against the background white of the stone’s dominant matrix.

There are many other image elements apparent as diagrammatic features here; for instance, the overall shape of the microblade core is that of a person’s head, shown with their eyes tracking the course of the microblade’s escape from the core, in a direct line away from their nose. However, I wish to concentrate at this point upon the intensive ordinates inherent in these images, for these are the aspects of image writing that most directly support the creation of the conceptual structures we are seeking. In addition to the carry-over of the mountain goat’s horn between the first and second image areas or “feathers”, we can also note a continuity in the intensive ordinates invoked of either case — that of “jumping”, of the mountain goat at the moment when a spear is most accurately thrown, and of a microblade from its obsidian core at the moment when optimum pressure is exerted through the tool used to pressure flake microblades from the core.

There is a subtle shift evident here in the temporal dynamic that divides the differences-in-kind embodied by each feather: in the first case, we have a leaping arc between both initial moments — of the spear’s throw and the mountain goat’s leap, and the final moment when either (or both) land; whereas in the second case, the defining moment of temporal division-in-kind is when the increasing pressure at the edge of the microblade core causes a single blade to detach and leap away from the core.

If we were to consider that the point of the mountain goat’s horn or the deer’s antler leads the animal’s leap, then we would have a dynamic that also becomes manifests as microblades are pointedly sent leaping from their obsidian core; but it is a dynamic wherein the intensive ordinate under consideration occurs in the second instance as an inverse of the first. Initially, the horn or antler as part of the animal is in front of and leading the leap; but separated from the animal and used as a tool, it is behind the leap of the microblade both figuratively and literally. Having noted how perceptions are differentiated from memory within the same processual neurology through a process of 'rotation', it is tempting to wonder if we are encountering here visual evidence of this.

It is interesting that this inversion — from a duration aligned across coincident moments, to a duration marked in a moment of sudden change — is accompanied by a mirrored inversion of image: between the white microblade outline on the black background of the microblade core; and the black microblade, shown against a white background as detached and in flight away from the microblade core. Conceptually, this inversion isn’t something that is inherent just in the instances of the microblade’s depiction: it also holds between the first and second “feathers” — between the horn as separated from the mountain goat, and the horn as separating the microblade from its core. Indeed, in this transition from spear point to microblade, the technology of stone tool production itself underwent an inversion: from removing flakes from a stone to produce a tool, to using flakes removed from a stone AS tools themselves. It is also tempting to speculate whether we are in fact examining a relationship between the dynamic of a perception — the sudden jolt of a leap — and the formalization of a memory; and that perhaps we have visual evidence here of how a memory might be rotated from a perception. If this is the case, then, we may be seeing evidence of how 'rotations' might be actualized conceptually, demarcating visual transitions from the experiential immanence of direct perception to the transcendence of conceptual structures that are retained as memories — now made intersubjective through anametric image writing. Remaining for the moment with conceptual structures informed within conscious awareness by grid cell modules, it is interesting to consider if the "orientation" processes of grid cells might play a role in informing the differentials presented through intensive ordinates, in ways that extend beyond a simple distinction between memory and perception.

What we can say with certainty, though, is that here we have an array of those aspects Deleuze and Guattari identify as characterizing the occurrence of conceptual personae: diagrammatic features that are in a state of immanence; intensive features that conceptually connect these features; and intensive ordinates that function as event-signatures, localizing the durational position of any temporal transitions that differentiate individual conceptual structures through their differences-in-kind. Again, we are dealing with grammatological functions that produce differentiations which are temporal in nature. This is a base situation very different from the quantifications that informed the kind of determinate relationships of measurement, which subsequently provided a correspondence model that, in grounding the core principle of semiology, allowed phonetic writing to be developed. And yet, both systems of writing — although functionally very different from each other — began from situations circumscribed by the production of food; and, both proceeded through ascriptions of personal identity. And in either case, we can apply aspects of ‘cognitive archaeology’ to gain some understanding of how each system of writing developed, as different as they are from each other.

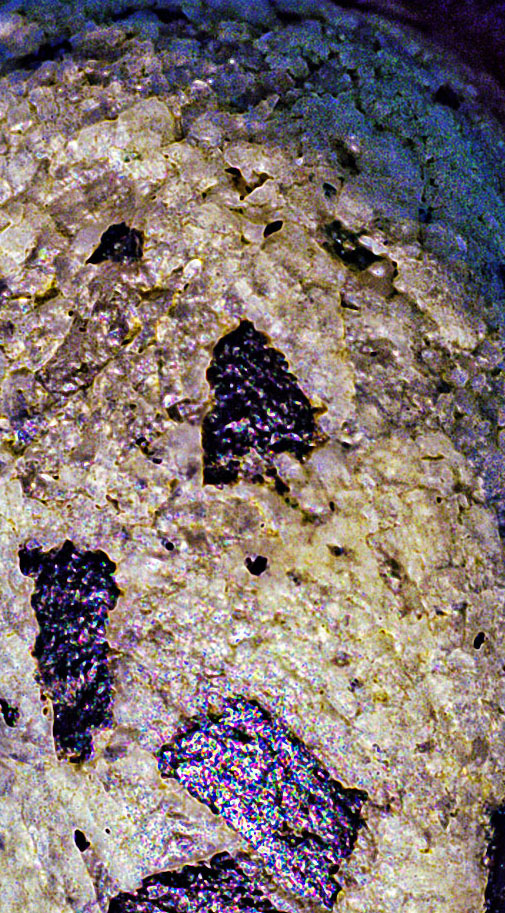

In the case of the obsidian microblade core, grouping that image element (as the “second feather”) with the one which follows it creates an image assemblage which presents the outline of a giant halibut. The “third feather” represents a granite hand ax, and provides a tail for the giant halibut. The white image details on the microblade core now become the mouth (from the horn tool), and the eye (from the flaked microblade), of the giant halibut (having worked at a shore processing plant in Vancouver, I’ve unloaded trailer truck loads of frozen giant halibut — that’s definitely one). Thus, while the spear point of the “first feather” is associated with hunting land animals, the microblade core of the “second feather” and the granite hand ax of the “third feather” are associated with harvesting ocean resources. Here, though, the relationship between production and food source is much more involved than it is with the initial spear point. Let’s consider for a moment the complexity of such tool production.

Obsidian microblades are up to a hundred times sharper than surgical steel, and these small pieces of volcanic glass could be produced in a very uniform manner through the pressure flaking technique of microblade technology. Through the use of advanced skills, microblade producers could also create flakes of different lengths (using different sizes of cores, prepared specifically for one type of output or another). Certainly, very long and lethal tips could be created for spears; but smaller implements could be created for fine cutting as well. Any length of microblade could be hafted into a wooden shaft or handle; but, multiple, small microblades of the same size could also be set into the same handle to create a very effective saw.

The invention of microblade-studded saws suddenly made available an incredibly vast resource, in the form of wood from trees otherwise too large to be utilized without such technology. Being able to utilize the immense trees that grow on the Northwest Coast would allow people there to build large seagoing canoes big enough for communal use — if they also had access to axes and adzes that were solid enough to withstand the stresses produced in hollowing out a massive tree trunk. Granite is certainly coherent enough for this kind of tool, but the integral nature of that very solidity makes flaking granite an impractical technique for creating granite tools. A different approach is needed: granite must be cut, using sandstone files and the same sawing motion used with microblade saws when cutting through wood.

Our granite ax isn't a particularly complex object; but like the spear point (with its parallel lines of breakage) and the microblade core (with the pressure tool and the flaked microblade), it does have a distinctive diagrammatic feature that is internal to its image area, and characteristic for the material production appropriate to this tool. We can take note of the place where the handle attaches to the ax, which is clearly indicated; and so, we know in which direction the ax is pointing. As simple as this diagrammatic feature might be, that an orientation it expresses is already evident distinguishes it as an intensive feature — an aspect that earlier observations indicate may point toward more involved complexities, as intensive ordinates.

Knowing now that this image writing compositionally forms grouping patterns of image elements, and moving in the direction the ax is pointing, we immediately come to another image area: one which appears to be that of a large feline. Indeed, the granite ax we started with is itself also the head of a large cat; but it is difficult to say exactly what species we are dealing with, because of the emphasis that is placed upon the incisors in each image. They are evident as etched in outline when the granite ax is taken as a big cat's head; they are obvious as white details shown prominently protruding from the mouth of the second big cat; and if we follow the second cat's line of sight, we find a third large cat, sitting in repose, looking toward the first cat-as-granite ax — with prominent incisors again shown as white details.

It is tempting to identify these large predators as saber toothed cats; but, their incisors are not at all long enough and simply do not compare with those of other images which are definitely of that species. Similarly, any inclination toward calling these large cats North American lions is undermined by the fact that their incisors are actually a little TOO prominent when compared to other images of that species. However, there were numerous species of large cat prior to the end of the last glacial age — some of which had incisors of a length somewhere between the Saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis) and the North American lion. Perhaps these images are of a minor species of big cat that I am not familiar with — such as the Scimitar-toothed cats (Homotherium serum) — of which few intact skeletal remains have been found. Of those rare finds, one in particular stands out in the paleontological record; and that instance includes skeletal remains of young mammoths. Since the eye assemblage of the Three Feather Chief’s face accentuates a young mammoth as prey, this may substantiate such an interpretation.

“Homotherium serum, while likely capable of taking on many types of large prey, seemed to specialize in taking juvenile mammoths as well as mastodons: distant relatives of both mammoths and modern elephants that were also massive in size. It is known that Homotherium serum had a large nasal passage for deeper breaths and claws that didn't retract for traction. It may have relied on short bursts of tremendous speed and power. It was better adapted for running than Smilodon. It may have also used these adaptations for dragging its prey to a safe spot to eat. Friesenhahn Cave: A cave near San Antonio, Texas. This is the only place complete Homotherium serum specimens have been found. Remains of baby mammoths and mastodons have been found here as well in large numbers. These were likely brought here by Homotherium in order to protect their food from scavengers, like Teratornis and the Short-faced Bear. This behavior, called denning, is seen in some modern predators as well [Benson, Andrew; Daggertoothed Cats].”

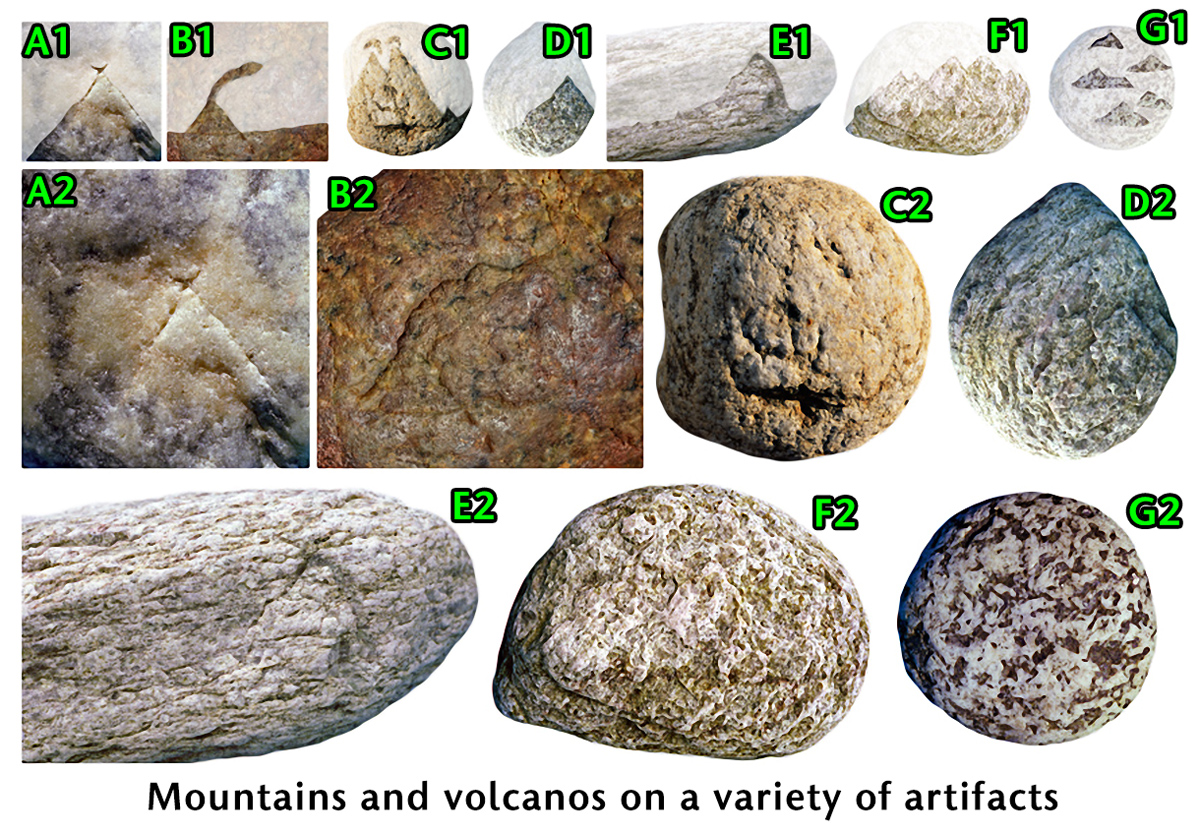

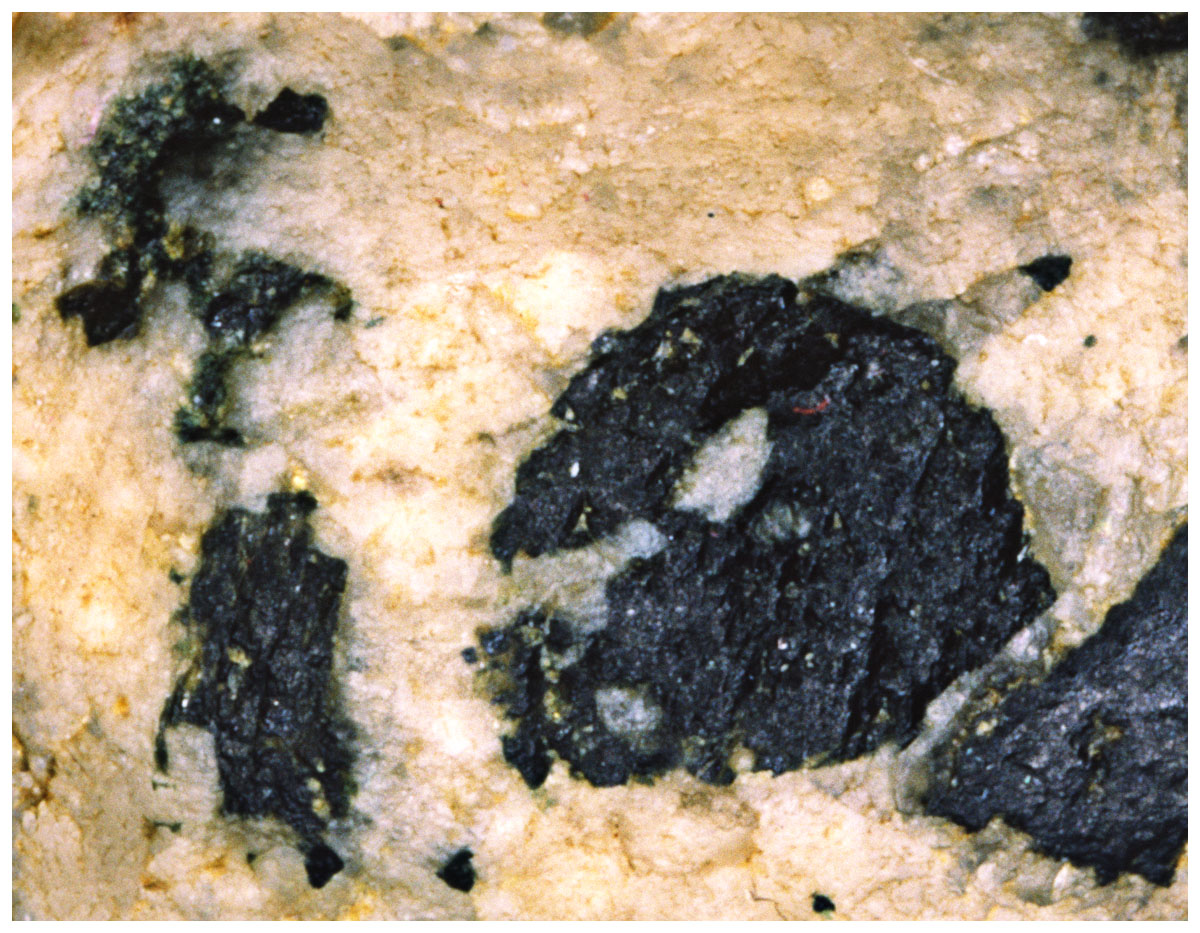

Artifact Image

Artifact Image

Whatever species of big cat these three might be members of, it seems apparent that they were social. In that they are shown as following each other's lead, it seems reasonable to assume that they would at the least hunt together when the opportunity or need arose — even if they each tended to range individually.

One might suspect that, taken together, the images of these three large cats would form a composite face (such as that of the Three Feather Chief). And indeed they do — but it is not the face of a large cat. Instead, these three big cats, as image elements, compose the face of — a bear.

This shift in species type might have seemed to present a bit of a conundrum to our ongoing interpretive efforts, had we not by this point become accustomed to the fact that no image elements have any simple, single identity within anametric image writing. Instead, we have seen time and again how finding shifts between differences-in-kind will allow us to gain insights into the ideas being conveyed through image writing — and this example is no exception.

Let's start by taking the third big cat — the one shown in repose — and rotating the image composites we are viewing around that area. We immediately see that this image area quite definitively becomes the nose of a very alert bear — one intent upon something that is in the general direction of the viewer. The bear's two eyes, above and equidistant on either side of its nose, are nicely detailed with white highlights reflecting from the center of each eye's black image area. And although a bear's nose is larger than its eyes, in this case the disproportionality seems somewhat pronounced — as if the bear's tendency to rely upon its sense of smell over its eyesight is being highlighted, perhaps implying that the bear is still at a distance.

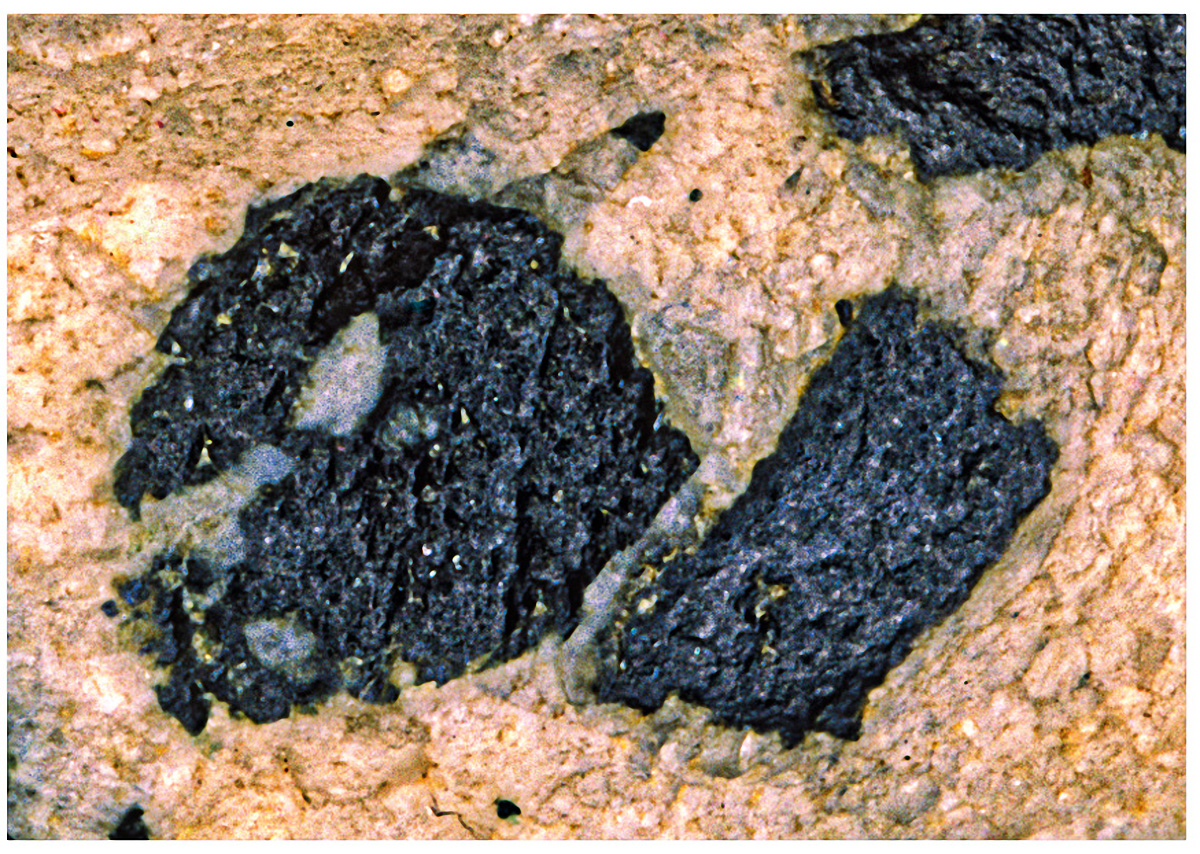

Artifact Image

Artifact Image

We don't need to guess the bear is smelling — it smells the giant halibut. Indeed, a slight shift of the grouping pattern for these image elements reveals that the bear's nose articulates into an eye for a new composition of facial features — with the second big cat becoming the other eye, and the granite ax becoming the mouth.

The bear, smelling the giant halibut, has suddenly grabbed it by the tail!

This is indeed an interesting turn of events: the shift in the grouping pattern for these image elements has just shown us exactly the same sense of immanence we experience directly of our own consciousness! The image of this bear, in being articulated across two instances by a shared image element, is "varying from itself with being other than itself": in other words, we are being shown the immanent nature of this bear as a distinct species, as a difference in kind that is discernible only within time — and that also means, only through memory. In this, we might also say that these very rotations distinguish such images as memories distinct from direct perceptions — perhaps serving as mediating articulations of immanence which facilitate narrative shifts between the momentary perception of one image and its lapse into memory as the next image centers itself within perception. In terms of possible neural processing relative to grid and place cells, we are seeing grouping patterns shift as articulated upon shared image elements; and this shift, although necessarily presenting a durational differentiation of event between a "before" and an "after", once again demands we inquire of the nature that "rotation" presents, and how variable the expression of this roll might be in differentiating between perception and memory within conscious awareness.

There are in fact a number of things that readers of this specific example of image writing are being told to remember — not the least of which is that bears will try and take a catch of giant halibut if they have a chance to do so. Ongoing vigilance against such marauding bears is a prudent course of action — a point emphasized by the way the large cats keep sight of each other, acting in concert; but if a bear should attack, there is one course of action that is recommended here: to bash its nose with a large rock, such as a granite ax. Let's return to the giant halibut, and its granite ax tail, to see what intensive ordinates we can find associated with the diagrammatic features of the bear's face.

The intensive ordinates associated with the granite ax that seem to be most applicable to the nose/mouth of the bear are those related to the sawing motion used to cut the ax from a larger piece of granite (found in the back-and-forth motion of the bear's nostrils when it is 'sniffing' at something), and related to the action of flaking the area where the ax handle is attached (a hard, sharply forceful motion akin to a bear biting). Both of these intensive ordinates are heavy, solid, certain, regular, and direct...like the determined, ambling motion of a bear which smells fish. Noting that the bear's nose/mouth, the granite ax, and the fish's tail are all expressed by the same singularity, we can suggest the concept being expressed here: it is, simply, 'grabbing the tail' — an important part of fishing successfully for giant halibut. In order to land such a fish by bringing it into the canoe, you need someone who is 'as big (and strong) as a bear' to grab the giant halibut by the tail — with the same suddenness, force, and surety of a bear (in a heavy, solid, certain and direct fashion). This person must also be as attentive as a big cat, and as swift as an arrow.

And as mentioned, one other thing is being told to us here, related to the intensive ordinate of the bear's sniffing nose. Bears can be dissuaded from an attack by smashing them on their very sensitive noses. A solid granite ax would be better for this than anything else.

If we have a closer look at the other example referenced above, of the Three Feather Chief as tool maker, we actually find an image of exactly this happening: a bear is shown being hit on the nose. In effect, this information is cross-referenced between two examples of anametric image writing which both display the Three Feather Chief motif — yet another very strong indication that we are indeed dealing with a well developed form of writing that was in common use, and which can be characterized as being substantive in nature.

In the Three Feather motif, we see depicted a direct progression in technological advances, with each stage creating the conceptual conditions which enable the next development to be invented. The leaping motion of the “spear and deer” (or goat) assemblage leads to the innovative leap of microblade technologies; and the sawing movement used in utilizing microblades for working wood leads to the cutting movement of sandstone files used to create shaped granite axes and adzes. Together, these tool technologies enable the wood resources of the Northwest Coast of North America to be brought to bear in harvesting the maritime resources offered by the ocean; and in viewing this, we can say that the intensive ordinates we have noted in the Three Feather motif characteristically deterritorialize from each image area and reterritorialize upon the next, conveying the shift in food resources that occurs in each case. Here, we have a practical demonstration of what Deleuze and Guattari termed “geophilosophy”, and so note that we are presented with the experience of a world in which there is a deterritorialization from the mountains where goats are found coupled with a reterritorialization onto maritime resources.

Something else very interesting is happening here at the same time: when we traced the intensive ordinates between the image areas in the Three Feather motif, we found a differential recurrence of signature profiles that were being repeated across different instances — from mountain goat to microblade flake, and from obsidian saw to sandstone file. In distinguishing these intensive ordinates as individually distinct from the collective diagrammatic features that present them, we find ourselves employing exactly the same conceptual mechanism as that which establishes the Three Feather motif as itself representational for a specific conceptual persona — that of the Three Feather Chief. Instead of a personae being perspectively implied in terms of conceptual point-of-view, we have the dynamics of event-signatures transcending the direct experience of their occurrence; and again, we must wonder if these dynamics are in fact somehow indicative of the differential process which distinguishes perception from memory. In this, we see traces of the motivational transition from immanence to transcendence presented in such a way as to suggest that the 'rotational' differentiation which distinguishes perception from memory within the same processual neurology is in fact more accurately conceived of in terms of waveform signatures — something it seems anametric image writing is capable of capturing, expressing, and conveying directly. This is by no means a unique occurrence, and in fact appears to be a functional aspect of how this form of image writing conveys information. We can find the same process at work in the form presented by the giant halibut: there, we find two very different intensive ordinates being united as differential yet immanent within the same singularity.

The flaking and sawing activities associated with microblades are sharp and fast (as intensive ordinates), as are microblades in their use; those associated with a granite ax are hard (heavy) and slow (as is its production and use). What is particularly interesting here is the interpretive shift which occurs when the intensive ordinates of the microblade core and those of the granite ax are united as, respectively, the body and tail of the fish. Here we have differential intensive ordinates co-presented to express the immanent nature of an animal: the head of the giant halibut bites and snaps with speed and agility in unexpected directions; but the tail of the halibut pushes the fish through the water with a ponderous and slow, back-and-forth motion. In this, we are seeing the intensive ordinates which define the diagrammatic features presented, being employed to define the characteristic and temporally determinate difference-in-kind of an animal.

The grouping pattern of an image area’s primary singularity — its perspectival point-of-view, which had previously been employed to establish relationships between reader and writer (through, for instance, placing oneself in the position of the person throwing a spear at a mountain goat or flaking a microblade from an obsidian core) — is now being used to define the inherent temporal characteristics of an animal’s difference-in-kind, relative to the reader (and, of course, the writer as well). The animal’s difference-in-kind is being presented as an event horizon, one which defines characteristic durations through the intensive ordinates it naturally produces as its way of being-in-the-world; which are, in turn, taken as descriptive of activities uniting people — through their deterritorializations and reterritorializations, relative to the world — with that animal-in-the-world. Clearly, what we are seeing here is a conceptual formation that is distinctly non-subjective as well as transcendental, defining a field of interrelation such as characterizes writing in any manifestation.

Once again we see diagrammatic features displaying intensive ordinates through immanence, and processes of territorialization being laid out in such a way as to allow the formation of conceptual personae here; but we are seeing this happen through the characteristic durational dynamics of animals, not of people.

Perhaps, in using a form of image writing which is not dependent upon symbolic representations that stand in the place of phonetic vocalizations, once again we are actually gaining significantly more than we are losing; because now the geophilosophic relationships from which concepts are formed can be configured with immanences drawn from a multitude of differences-in-kind, which will radically diversify the territorializations expressed thereupon, and therefore increase the conceptual complexity capable of being supported therein beyond measure — literally, by definition.

I mentioned earlier how great of a divergence can form between a geophilosophic approach, which finds a world view through the things created for living within that world (or in this case, the other living things also inhabiting that world), and, an approach which defines people in terms of their relationships with the world (rather than the relationships between the objects they create and the world). In its initial institution, it is a subtle difference; but it is one which quickly becomes very, very wide — even for the most well-intentioned of approaches.

For context, I would like to step back for a moment and consider a few observations made by Mary-Jane Rust in her essay, Why Do Therapists Become Ecotherapists? (which I find to be disconcertingly of the ‘one size fits all’ variety; but then, post-structuralists often form that impression of psychology):

“If therapy is to extend its practice from being human centered to recognizing our relationship with nature “out there,” we need a concept of self that describes how individuals are inextricably intertwined with community and earth. Indigenous cultures have always recognized this, and their language to describe the self can inspire us to think outside the box of our culture. Okanagan Canadian author and activist Jeannette Armstrong describes here the concept of the self from the native people of the Okanagan tribe of British Columbia:"

“We survive within our skin inside the rest of our vast selves. . . Okanagans teach that our flesh, blood, and bones are Earth-body; in all cycles in which the earth moves, so does our body. . . Our word for body literally means “the land-dreaming capacity.” . . . The Okanagan teaches that emotion or feeling is the capacity whereby community and land intersect in our beings and become part of us. This bond or link is a priority for our individual wholeness or well-being.”

“When we see humans like cells within the body of the earth, we understand that our physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual health depends upon the health of our “vast selves.” This challenges our current Western notions of self in relation to the world, where humans are seen to exist on top of a revolving ball of dead matter. Instead, this indigenous concept of self sees humans as inhabiting a larger living body. As Ecotherapists we can draw on these perspectives to describe a self that extends beyond our skin — and ecological self that is in the same moment spiritual [Buzzell and Chalquist, Ecotherapy: healing with nature in mind, pgs. 44–45].”

Ecotherapy is still a nascent field, but it is one which (in my opinion) could benefit from an intervention from post-structural philosophy (as could all psychiatry; but, that’s another story). If we attempt to ask authentically, “How does ‘the other’ have an edge of discernment”; or, “How does Alterity become a differential?” then we are inquiring as to where the ‘self’ leaves off, and how the differential of this separation is determined.

As you no doubt will have noticed earlier, post-structural philosophy tends to approach, whatever "the self" might be, in terms of processes — rather than as a 'thing' or a steady state of being.

In considering Indigenous cultures — specifically that of British Columbia’s Okanagan, as presented above — Mary-Jane Rust suggests seeing individuals as if “cells within the body of the earth”; but, I would contend that this interpretation is one which the author is bringing to the discussion, rather than an insight that is being preserved within Indigenous culture. There is a very different interpretation that can be composed here (and one that really does align with innumerable First Nations stories): “The skin” becomes the (very sensual) surface of discernment, the differential through which Alterity is realized; and starting from ‘the animal skin’, or ‘the bird’s feathers’, we find that the world around such other beings is very different than that which surrounds us. In effect, there is a geophilosophy for each that articulates upon their engagement with the world; and precisely because the world is encountered through a different interface, a different surface of discernment, each has a world about them that is distinct from the world of any other.

Such an interpretive approach would be more consistent with Bergson’s conception of temporality as dividing up through differences-in-kind, and would render the world as a multiplicity of differences rather than a unity of measured extent; but we are not going to find ourselves party to that kind of world if we phrase our expectations of this exclusively in terms draw from the phonetic forms of writing that today dominate the world.

Anametric image writing, as it developed in North America, offers a very real and tangible alternative to the world views determined through phonetic writing as we now know it; and it can be quite a surprise to realize how far this form of image writing evolved.

The distinct image areas of the Three Feather motif present a material history of the technological advances developed, for the production of stone tools, by The Three Feather Chief’s people. At the same time, specific relationships are outlined between the forms of tools being created and used, and the types of food resources made available through the use of these tools. In other words, there is a direct relationship established here between production (in this case, of tools) and food resources — a relationship also seen in the Near East, as grounding in the production of agricultural surpluses the conceptual advances that eventually facilitated the invention of phonetic writing. Once again, it is possible to find a clearly shared conceptual commonality holding between the development of image writing in North America and the invention of phonetic writing in the Near East.

The kind of continuity seen here between specific examples extends much farther, to embrace the entire historical record this form of image writing preserves. Taking each productive technology as emblematic of a distinct age of image production, whereby a direct relationship exists between the forms of tools produced, the types of stone used in their production, the material substrates used for creating images, and the overall form taken the images so created, it is possible to envision three distinct epochs of development for the evolution of image writing in North America.

If the developmental trajectory of material innovation depicted by the Three Feather motif is one whereby the efficiency of tool production is steadily increased, the ultimate solution reached was to use granite and to cut it using sandstone — a type of stone that wears away easily, taking away some of what it is applied against in the process.

If we consider the use of granite as the material substrate for anametric image writing in its most advanced developmental form, we are presented with a very interesting definitional dynamic for temporality as defined with reference to the production of image writing: one wherein the present endlessly effaces the past, incorporating it into what becomes next but, is presently hidden. This is a very different dynamic than that which informs Western European patterns of speech, where one instead sees a future that builds upon the past, in a process of steady increase. In the first case, we have a situation that demands a dynamic balance be maintained in the present between what has been and what is to come, least both be lost forever — an approach which is entirely consistent with a culture that needed to survive, through the rigors of an ice age, by very selectively harvesting resources in a sustainable way from the few scattered refugia that had escaped the peak of glaciation on the Northwest Coast of North America; and in the second case, we have a dynamic grounded in the endless bounty of ever increasing harvests, and which mythologizes such endless increase — and that consequently underwrites an eternal taking of profits.

Since we can trace the material advancements grounding First Nations culture through the development of technologies for the production of stone tools; and since we know that the type of stone used as a substrate for anametric image writing directly influenced the formalization of that writing system; and since, by definition, "The Historical" is constituted precisely by a culture's written records, we can also say: the developmental horizon of First Nations material culture establishes and defines the Historicity of that culture, in grounding the production of anametric image writing.

Here, we can speak of a material culture; material narrative; and, a material history.

The end solution to the problem of tool durability also resolved into the use of a mediating substrate for anametric image writing that is pretty much indelible. Today, the paper used for writing might last a few weeks if left exposed to the elements. anametric image writing on granite can easily last tens of thousands of years. How much paper would there be piled around right now, if everything with writing on it from the last 500 years was still sitting on the ground? Now multiply that by a factor of at least 40, and you will have a rough idea of how common examples of image writing are throughout North America: they are not difficult to find — for anyone who looks with an open mind.

It takes a willful blindness on the part of professionals in the archaeological and anthropological communities not to see this — the same sort of willful blindness that racial inequality demands in order to be systemically perpetuated.

Returning to the insights afforded us by Félix Guattari in his essay The Role of the Signifier in the Institution, we can now consider how we can incorporate the concept of “matter” into the linguistic analysis of this image writing, and examine the relationships holding between the material substrates used in its production, and the form into which this writing evolved.

Two very basic observations indicate how best to proceed in this: that the physical properties of the stone substrates used when creating images had a direct influence on the nature of the image writing produced; and that stone was primarily used in the production of tools. In considering these two points, a third observation immediately becomes apparent: with reference to the Three Feather motif, that we know there was a developmental evolution in the technologies used to produce stone tools — and that this corresponded to shifts in the types of stone being used in the production of tools.

If we consider the production of image writing in terms of Substantiation — that the production of any stone tool demanded a close inspection of the stone matrix being utilized, to determine its specific properties as an identifiable substance as opposed to its generalized existence as a form of matter — it stands to reason that we might be able to trace the development of anametric image writing through an examination of the stone substrates used in its production. If the mediating substrates used in the production of images shifted along with the type of stone used for the production of tools, then this could present a viable approach for mapping the evolution of anametric image writing.

This is precisely my contention.

I would propose, then, that the horizon of historicity most proper to First Nations culture is one which is resolved within the context of their own writing, rather than one that is imposed from academic determinations derived from Western European traditions. Since “prehistory” is, by definition “… the period from the time that behaviorally and anatomically modern humans first appear until the appearance of recorded history following the invention of writing systems”, we must immediately recognize the arrogance and absurdity of defining the historicity of First Nations culture exclusively with reference to the phonetic forms of writing which are native to Europe: indeed, this is precisely the approach that drove the cultural genocide visited upon the First Nations by way of the Residential School System.

To ignore the historical horizon of the First Nations as defined by their own system of image writing is quite literally a crime against humanity — ALL of humanity, given that the writing system invented by the First Nations of North America appears as the beginning of written history.

To clarify my position, I am not trying to “prove” anything here: I am simply attempting to trace the contours of a historical progression using the evidence at hand, as best I can, to construct a viable hypothesis that can be compared with and tested against actual examples of image writing — both now, and in the future.

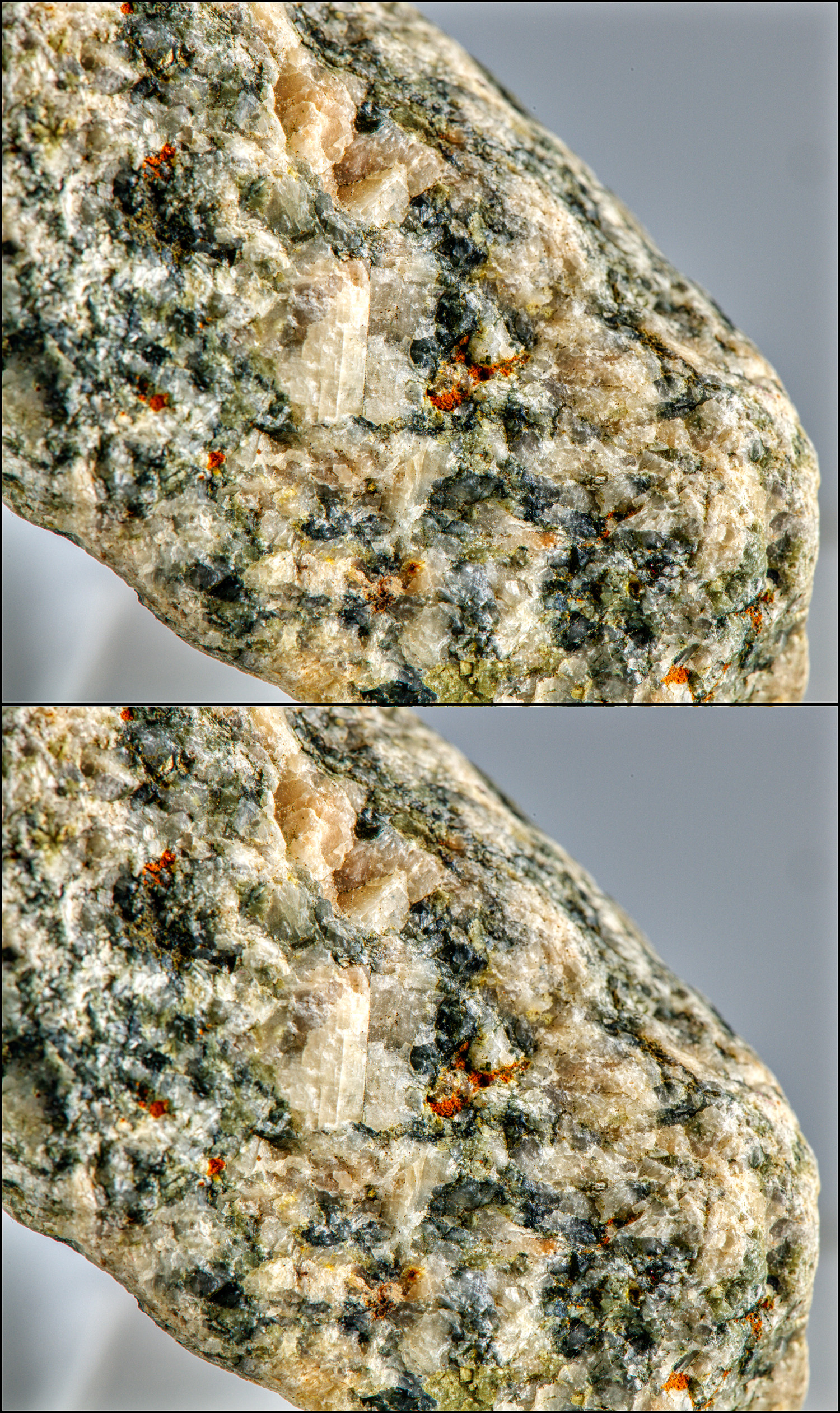

Not surprisingly, it is not at all easy to find examples of the earliest form that image production took in North America just lying around. In fact, it is almost — although not quite — impossible. Nonetheless, I do very fortuitously have one such example, in more or less pristine condition. This, I found in association with the other oldest example I have — the one I am fairly certain was created and used by an as yet unidentified species of hominin that inhabited North America from some unguessed earlier era.

I strongly suspect that the example I am about to show you was obtained from early human arrivals by such a hominin, who secreted it away with along with an example of his or her own species’ production; but, I don’t see any way of proving that conclusively (and I am not going to go into the grounds for my suspicions here). I will simply state in passing that, with my back brushing against an overhanging rock wall as I moved along a ledge overlooking the ocean, these examples literally fell at my feet. If I hadn’t picked them up, they would have been lost forever; if I hadn’t happened along to bump into them, then rising sea levels would have claimed them before very much longer. I decided at the time that this event was too singular in my experience to simply leave these stones where they fell; although, looking at them, nothing immediately caught my eye as characteristic of other examples of image writing I had encountered by that point.

As noted with reference to the Three Feather motif, the earliest era of material production for the First Nations in North America was characterized by the production of simple stone tools that were made in a one-off fashion: one piece of stone was used to produce each tool, with the stone being shaped progressively, as more and more flakes were removed, until the desired tool was all that remained.

Examining a very early example of image production in North America, we find that there is indeed a correlation between the sophistication of the tool production techniques being used at the time, and the complexity of the images being created at the same time.

In placing this very early example within the context of history, we immediately find ourselves in a perplexing situation: inferentially, if earlier considerations regarding the use of microblades in North America are correct, then two possibilities must be addressed here: either this particular example was created very early on in the era during which microblades were produced and used, or, humans arrived in North America prior to the invention of microblade technologies. If the former is the case, then questions arise as to how long the use of early stone tool technologies persisted in North America; and if the latter is the case, then there is also the chance that microblade technologies were first invented in North America, before then being carried back into Asia — and at that point, it is anyone’s guess as to how very long ago the first people arrived in North America.

I might tend to lean toward the former interpretation, in that this stone was found far to the south of where the first active volcanoes would have been encountered by those arriving earliest in North America; but on the other hand, there are aspects of this very early example that seem to suggest it originated far to the south, in the area of the Grand Canyon — implying that people were in North America before the peak period of glaciation, and followed the retreating ice sheets north, to once again reterritorialize the Northwest Coast — perhaps as yet more people arrived from Beringia, by way of watercraft. Of course, whatever we might reason of these matters must always be secondary to the contingency of what actually happened — and we really don’t have enough information to discern that, accurately.

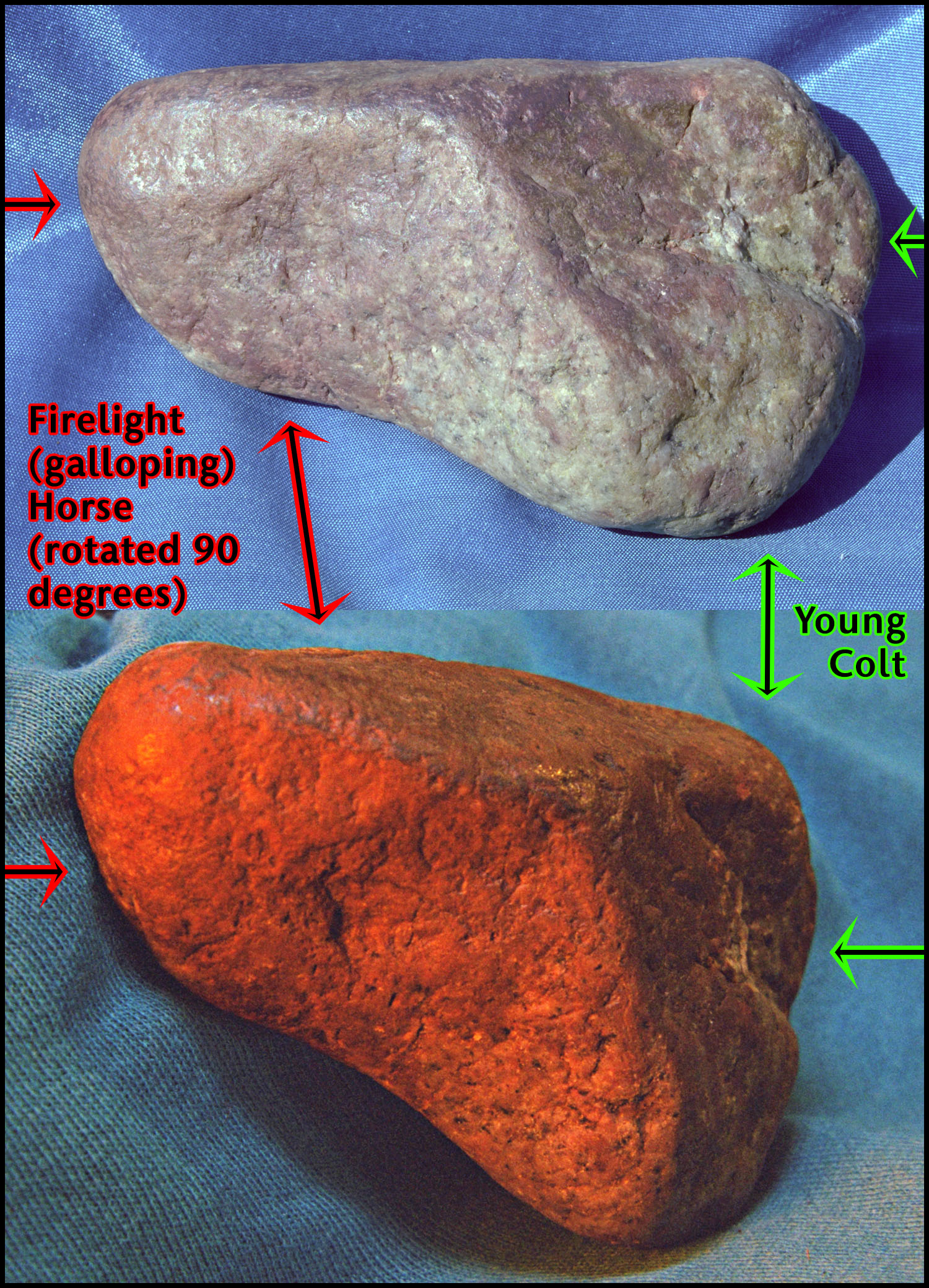

What we can say for sure is that the person who created the images upon this particular stone saw erupting volcanoes. They also saw horses. They also saw lions; indeed; they identified with lions (which one must assume were North American lions); and this is an observation which is consistent with that of the hominins who initially encountered the first humans to arrive in North America. Examining the images upon this stone, we find that, although the use of imagery was not overly sophisticated — images seem to be singular in nature, and do not appear to be articulated together into the intricate composites that characterize later epochs of image production — the techniques employed and the skill behind the execution of these images were very advanced.

The stone itself has been sculpted into a distinct shape; and this is consistent with stone tool technologies which would have been directed toward producing singular tools from single pieces of stone. We can also see how the image of a child has been very skillfully carved in relief on the surface of this stone, a fact best revealed with a distinctly directional light source. Indeed, the creation of images upon this stone seems intimately tied to the lighting conditions under which this seems to have occurred: there is a particularly beautiful image of a horse at full gallop that is most easily evident when viewed by firelight.

Artifact Image

Artifact Image

Artifact Image

Artifact Image

Whatever else we might learn from this very early example will be left for future study: my primary purpose in presenting this here, is to provide a baseline example with which to compare later instances of image writing. In any event, we should keep in mind that there does seem to be at least a tentatively direct relationship between the stone used — that is, the material epoch in which this example was produced — and the form of the images created upon its surface.

In examining the microblade core depicted in the Three Feather motif, we noted a shift in the technologies being used to produce stone tools — and a correlated shift in the type of stone being used in the production of tools. We also noted a distinct conceptual shift occurring: from the idea of using one stone to produce one tool, to that of using one stone for the production of multiple tools. This was very much the case with microblade cores and the multitude of tools flaked from each; but it was also true of another approach to stone tool production, one which would forego the use of sharper flints and other such stone in favor of duller slates and other sedimentary stone — because, stone that formed in layers could be used to produce multiple tools from a single rock. By shaping sedimentary stone appropriately, and then separating the layers into individual tools, as many copies of a tool could be made as there were layers within a stone. In this way, it was even possible to produce different kinds of tools using the same stone: by sculpting a stone into the generalized shape of a small animal’s skull, for instance, both spear points and arrow heads could be made at the same time; and after the stone was separated into its constituent layers, all that remained to be done was imparting an edge to each of the resulting stone blanks.

Recall here what was noted in previous sections, in the context of stone tool usage: slates and other such stone, although duller than flints, provided a more efficient source for tools in being less prone to breakage during use. It is precisely the amount of time saved in the production of new replacement points that makes the use of slates more efficient overall — an efficiency greatly enhanced by producing multiple copies from a single stone.

It is difficult to say whether this approach to tool production predated or followed that of microblade production: the basic skill sets needed were in evidence with the First Material Epoch of stone tool production, but the conceptual context might be more strongly associated with advanced approaches to utilizing wood resources (in that wood can also be separated into layers when pounded by a heavy stone); so that question might end up being answered in either direction. Clam shells also have somewhat of that same characteristic layering as wood, so these may have provided the inspiration for this approach to stone tool production — and we do know that shellfish were utilized as a food source very early in the history of the First Nations on the Northwest Coast of North America.

I will note that examples of image production from this, the Second Material Epoch, are a little easier to find than the first. Of the few examples I have which appear to be from this time period, several are roughly shaped as shellfish (oysters) would be, and exhibit image production defined by the edges of the individual layers that compose the mediating substrate. Something that I find particularly interesting is that later examples of anametric image writing found on the opposite side of continental North America retain aspects which are suggestive of First and Second Material Epoch production techniques — even as those Third Material Epoch examples clearly differentiate from Northwest Coast examples also dating into the the Third Material Epoch; an observation which hints at the point in time when people left the Northwest Coast, to radically expand across North America as the glaciers receded.

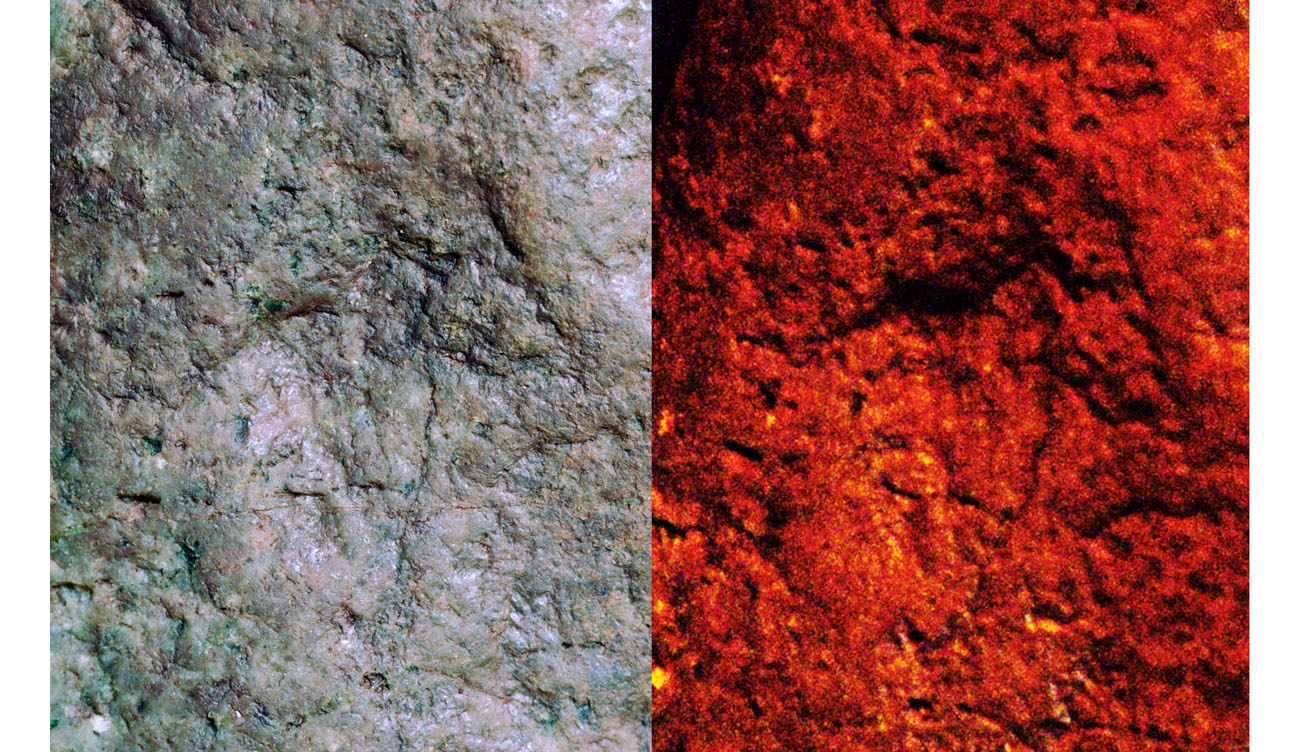

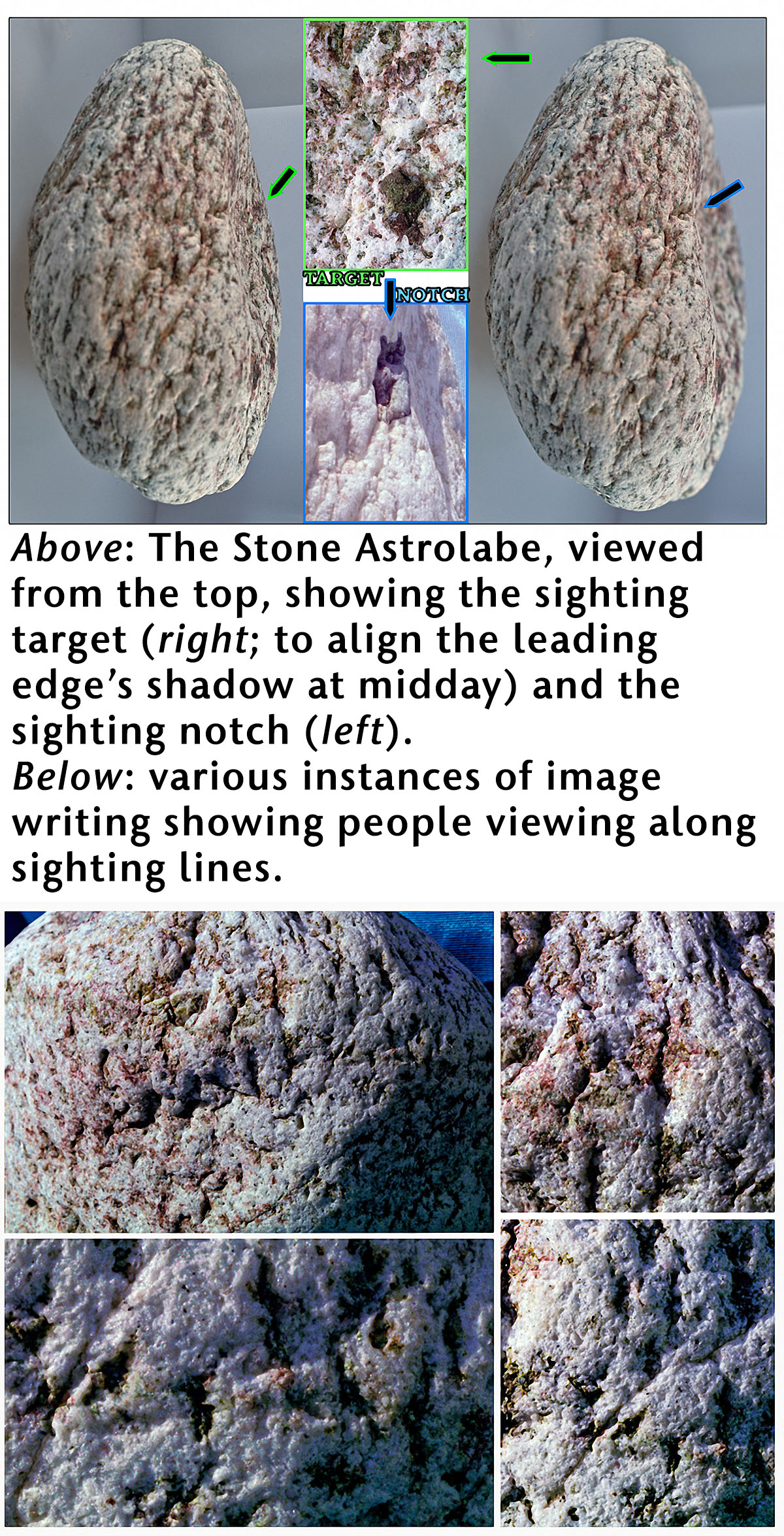

I have one particularly important example of Second Material Epoch image production from the Northwest Coast: a Stone Astrolabe. This particular stone, shaped like the ear of a North American lion, is sculpted in such a way as to highlight different images in accordance with the height of the sun (when the stone is pointed toward the sun at midday). Much less worn and weathered than the other examples I have from the Second Material Epoch, this Stone Astrolabe seems to have been handed down from person to person, for unguessed millennia before it came to me (a supposition which would be consistent with the rather strange way it came into my possession). The other examples I have were lying around for just as long; and, it shows.

Examining these examples, the overall shape of an ear is prevalent — apparently suggesting, of course, a relationship between speech and writing that is to be expected. It has long been known that the First Nations maintained an oral culture of story telling; but this is not by any means counter-indicated through the existence of anametric image writing, which would need to be verbally interpreted in order to be shared beyond direct viewing and reading. Very early examples might also be construed as having the shape of mollusk shells, which is an abundant and readily available source of food along shorelines, and one that was not subject to seasonal fluctuations in availability. If the first people to arrive in North America did so by skirting coastlines now long-submerged, then this would naturally have been a favored food source. To this day, the First Nations on the Northwest Coast have a saying: “When the tide is out, the table is set”; and origin mythologies involving mollusk shells are well know from this area. Shells always exhibit ridges of annual growth that are very reminiscent of the layers in sedimentary stone; so perhaps the shell shape is the primary one, with the ear shape being secondary; but there is no reason why both would not have been in conceptual play when these examples were produced.

Looking at the images upon these particular examples, we find that there was a definite tendency to sculpt characteristic shapes along the edges of individual layers in the stone. This is entirely consistent with the way that tools were being produced from similar pieces of sedimentary stone, with sharpened edges being added after each layer had been separated into individual tools.

When we get to the much later example of The Stone Astrolabe, we find something very interesting has happened: in addition to the stone itself having been sculpted in relief, the images produced upon it have become reduced to silhouette-like schema; and these were incised through the surface layer of stone into an underlying layer of darker color. In effect, where sculpted images were earlier joined through sharing the edge of a common layer, now a surface of images are all co-joined through an underlying commonality that also defines their expression: it is by way of the darker stone coming through the lighter stone that all the inscribed images appear as implicitly connected together — that is, as more or less immanent to each other. It is not through sharing a single surface layer that the images are connected: they are being connected through a subsurface layer that they hold in common.

It is easy to see how, conceptually, this development most closely aligns with the use of multiple microblades in the formation of a single tool (such as a saw); and this suggests that the period of tool production which utilized sedimentary stone, and was associated with shellfish harvesting along the coastline, preceded the period in which microblade technologies were utilized. So again, we have the dilemma of a coherent timeline to contend with: if we say that microblade technologies were introduced to North America after the end of the last period of glaciation, then we are at a loss to explain how images of animals that went extinct at that time are found in profusion upon examples of image writing which clearly date much later than The Second Material Epoch; but, if we date the introduction of microblade technology to North America much closer to the point where it first occurs in Asia, then we are looking at a strong indication that people arrived along the Northwest Coast of North America BEFORE microblade technologies were invented. Complicating such dating even further is the occurrence of what appear to be leaves from maize (corn) plants on the Stone Astrolabe — again suggesting that people moved into the area of the Northwest Coast from much farther south, at a time when European history doubts anyone had yet to venture into North America, and indeed would not do so for at least another 10,000 years.

Be that as it may, and however this issue resolves, our primary concern here is an analysis of anametric image writing; so let’s leave the dating of a timeline for this behind, and focus upon the developmental evolution of anametric image writing. We can see that by the late stages of The Second Material Epoch, all the necessary components were in place for us to be able to say that we are indeed looking at a form of writing: images are being produced as composites that articulate conceptual structures, and they are compositionally unified through a common shared substrate that defines their expression. If this were as far as image writing developed, it’s production and use would still constitute a form of writing in itself; but, its development didn’t stop there — an entirely other epoch of material production followed, and it is by far the most substantial of all.

We found in our examination of the Three Feather Chief motif that a final, third stage in the production of stone tools was eventually reached — one which utilized solid granite to produce very sturdy and long-lasting tools. It is when we consider the image composites that were produced using this material substrate that we begin to see how truly advanced anametric image writing actually became.

We noted of The Second Material Epoch how images, in being inscribed into sedimentary stone, were being connected together by virtue of a common shared substrate within the stone, below its surface. This was not the case with The Third Material Epoch: granite has no such layers, but only a chaotically random profusion of variance in the grain patterns constituting its stone matrix.

Now, chaos occupies a very prominent role in post-structural philosophy — which is one more reason why, perhaps, such an approach is well suited for letting the image writing of North America emerge on its own terms. The chaotic elicits from post-structuralism a response that is as authentic as anything philosophy might manage to create: that of a dedication toward mapping, what can only be described as, consistencies. If anything can be said of what I have undertaken here, I would hope that at the least I might be seen as keeping a mindful eye open toward any consistencies which might prove to be characteristic for this form of image writing:

"The plane of immanence is like a section of chaos and acts like a sieve. In fact, chaos is characterized less by the absence of determinations than by the infinite speed with which they take shape and vanish. This is not a movement from one determination to the other but, on the contrary, the impossibility of a connection between them, since one does not appear without the other having already disappeared, and one appears as disappearance when the other disappears as outline. Chaos is not an inert or stationary state, nor is it a chance mixture. Chaos makes chaotic and undoes every consistency in the infinite. The problem of philosophy is to acquire a consistency without losing the infinite into which thought plunges (in this respect chaos has as much a mental as a physical existence). To give consistency without losing anything of the infinite is very different from the problem of science, which seeks to provide chaos with reference points, on condition of renouncing infinite movements and speeds and of carrying out a limitation of speed first of all. Light, or the relative horizon, is primary in science. Philosophy, on the other hand, proceeds by presupposing or by instituting the plane of immanence: it is the plane's variable curves that retain the infinite movements that turn back on themselves in incessant exchange, but which also continually free other movements which are retained. The concepts can then mark out the intensive ordinates of these infinite movements, as movements which are themselves finite which form, at infinite speed, variable contours inscribed on the plane. By making a section of chaos, the plane of immanence requires a creation of concepts [Deleuze and Guattari, What Is Philosophy?, page 42]”.

Any consistency imparted into such a highly variable substrate will need to be discerned of the chaotic, and cultivated into expression — exactly as conceptuality itself must be. Further, such expression will need to occur in a context of partial dimensionality: for, this particular material substrate never presents a simple two-dimensional surface as something readily available for the production of images. As a mixture of light and dark, large and small, transparent and opaque, this particular material always presents a surface that implicates a depth of half-seen shadows — suggesting new image outlines. Yet, never is any consistent depth defined, in which the resolution of a surface could be grounded. Instead, only a radical difference suffuses this mediating substrate: a metrical variance between light and dark, yes, but one which randomly varies both by position on and in the substrate; and by the viewer’s relative location, as well as through the lighting conditions under which the stone substrate is being viewed — and the personal experience of the viewer, through their memories. As a surface that always includes some part of the depth which underlies the readily apparent, this mediating substrate is always more than two dimensions yet, less than three full dimensions: it is of two full dimensions, with a fraction of a third; and as such, these mediating substrates from the Third Material Epoch of anametric image writing always present a fractal surface.

Examples from the Third Material Epoch of this image writing abound, and several — such as the Three Feather Chief stone — have been presented here. One question left to address, is: How long was this image writing in use? We have considered at length its beginnings, but — where and when did its use come to an end, if indeed it did?

To this end, I would like to consider here examples of anametric image writing collected from the areas around New York City’s harbor. These artifacts are from the Lenape First Nations culture, and they tell an interesting story — one which stretches from unguessed depths of time, forward to the period of first contact with European settlers.

The next example I will present here, from the Lenape First Nation, is notable in that it exhibits characteristics we have seen in our exploration of the Three Material Epochs: it is obviously a product of the Third Material Epoch, in that it utilizes a stone substrate of granite; but, it also displays a characteristic feature from the First Material Epoch: namely, that of a distinctly sculpted surface. I find it very interesting to note that examples of image writing I have found on the Atlantic Seaboard, and in areas of Canada that would have been heavily glaciated during the height of the last ice age, seem to have characteristics indicating a cultural divergence from examples found on the Northwest Coast at a point transitional between First and Second Material Epochs — with these cultural traditions suggesting that people were already established in North America before the period of maximum extent for the glaciers, and then moved North following the retreating ice sheets. In their own words, the Lenape note:

"The peace loving Lenni-Lenape are called the "grandfathers" or "ancient ones" by many other tribes and are considered to be among the most ancient of the Northeastern Nations, spawning many of the tribes along the northeastern seaboard. We were known as warriors and diplomats, often keeping the peace and mediating disputes between our neighboring Native Nations and were admired by European colonist for our hospitality and mediation skills."