Introducing Conceptual Personae

In invoking both perception and memory, Quiroga locates such processes precisely where Peirce would have his ‘personal observer’ placed: in relation to the perception of a thing, and the semiological element that ‘occurs in the place of’ any such thing. In addition, when examining the role ascribed to personal identity by Schmandt-Besserat during the development of phonetic writing in the Near East, we also find an analogous role apparent within anametric image writing. In that we can now contextualize the role played by references to personal identity within anametric image writing through an understanding of how facial recognition is processed by the neurology of vision, we again find that we need not try to frame the functionality of anametric image writing in terms dictated by phonetic writing. Instead, we find that the role played by personal identity (as identifiable within anametric image writing) presents us with the opportunity to inform our understanding of this particular form of image writing, by drawing upon information established through clinical research into the neurological processes responsible for our experience of visual awareness as an aspect of consciousness. In that Quiroga notes, relative to facial processing neurology, the presence of neural processes nearby which are responsible for the formation of conceptual space; and given that Derrida has provided us with a description of the grammatological nature of image-based writing systems which is entirely consistent with the functional nature of facial recognition, as clinically demonstrated by Doris Tsao: we are justified in at least exploring how conceptual spaces and personal identity might coincide — an area investigated at length by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in the form of “conceptual personae” — and one which, once again, does not by any necessity involve invoking phonetic forms of writing:

"The conceptual persona and the plane of immanence presuppose each other. Sometimes the persona seems to precede the plane, sometimes to come after it - that is, it appears twice; it intervenes twice. On the one hand, it plunges into the chaos from which it extracts the determinations with which it produces the diagrammatic features of a plane of immanence: it is as if it seizes a handful of dice from chance-chaos so as to throw them on a table. On the other hand, the persona establishes a correspondence between each throw of the dice and the intensive features of a concept that will occupy this or that region of the table, as if the table were split according to combinations. Thus, the conceptual persona with its personalized features intervenes between chaos and the diagrammatic features of the plane of immanence and also between the plane and the intensive features of the concepts that happen to populate it : Igitur. Conceptual personae constitute points of view according to which each plane finds itself filled with concepts of the same group. Every thought is a Fiat, expressing a throw of the dice: constructivism. But this is a very complex game, because throwing involves infinite movements that are reversible and folded within each other, so that the consequences can only be produced at infinite speed by creating finite forms corresponding to the intensive ordinates of these movements: every concept is a combination that did not exist before. Concepts are not deduced from the plane. The conceptual persona is needed to create concepts on the plane, just as the plane itself needs to be laid out. But these two operations do not merge in the persona, which itself appears as a distinct operator."

"These are innumerable planes, each with a variable curve, and they group together or separate themselves according to the points of view constituted by personae."

[Deleuze and Guattari, What Is Philosophy?, pages 75-76].

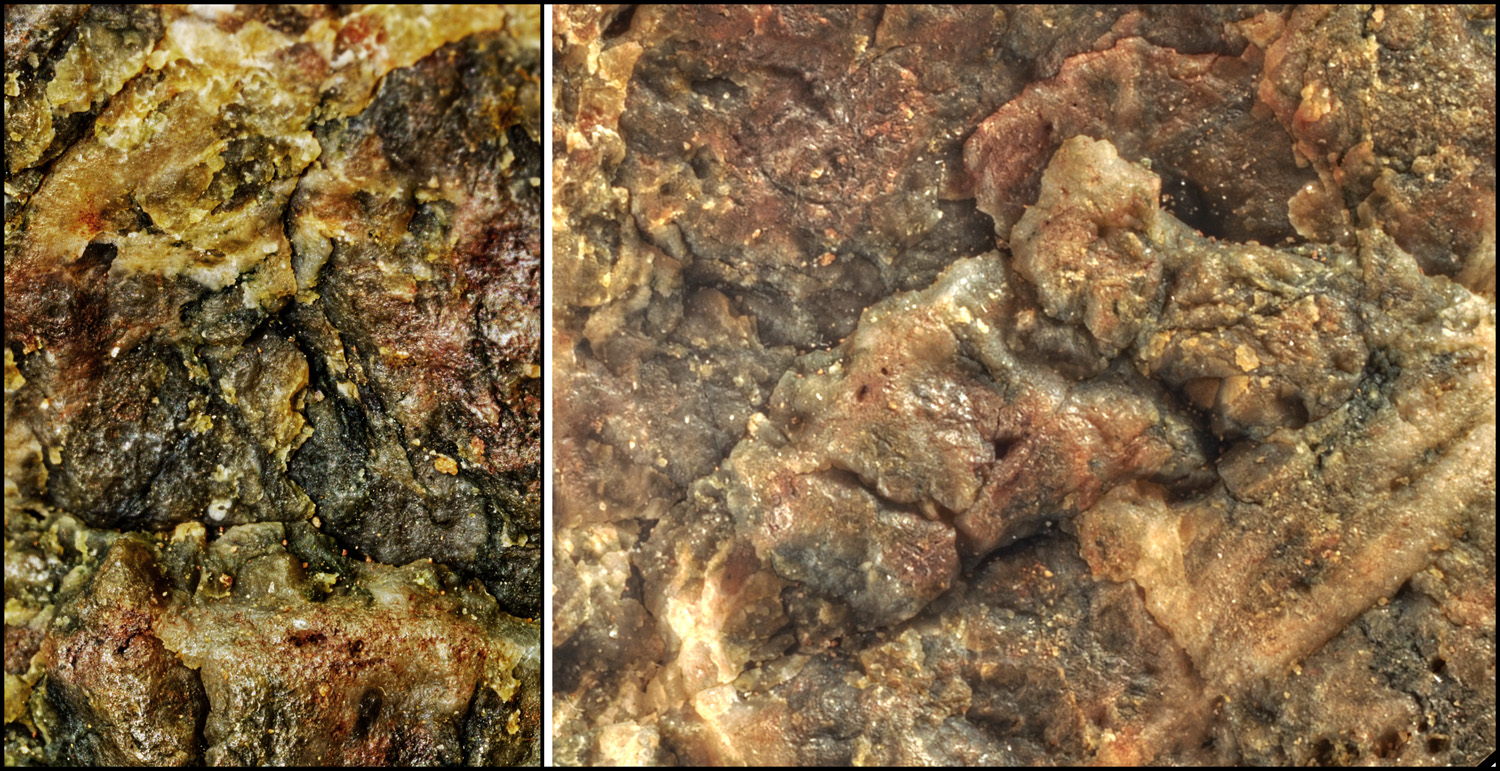

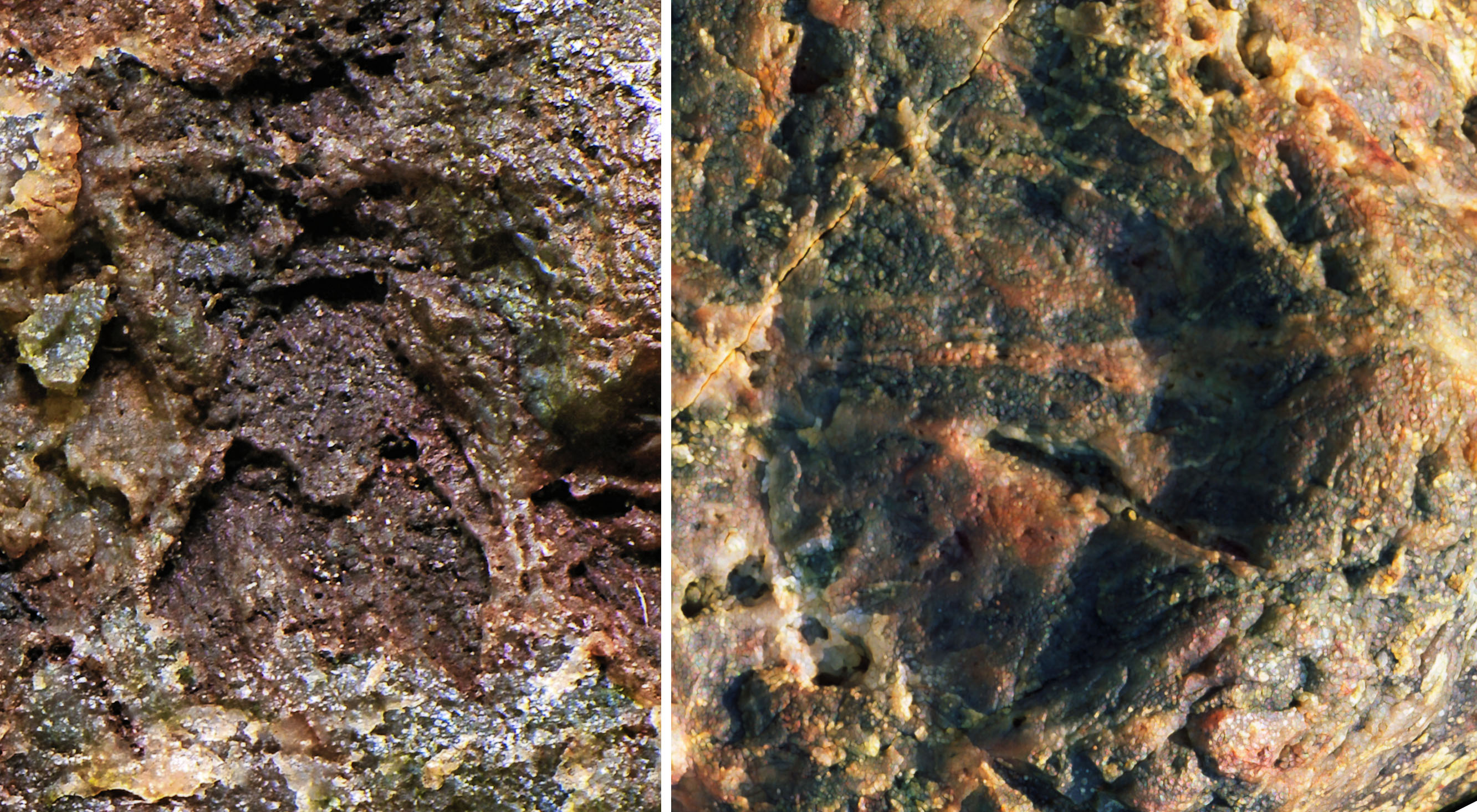

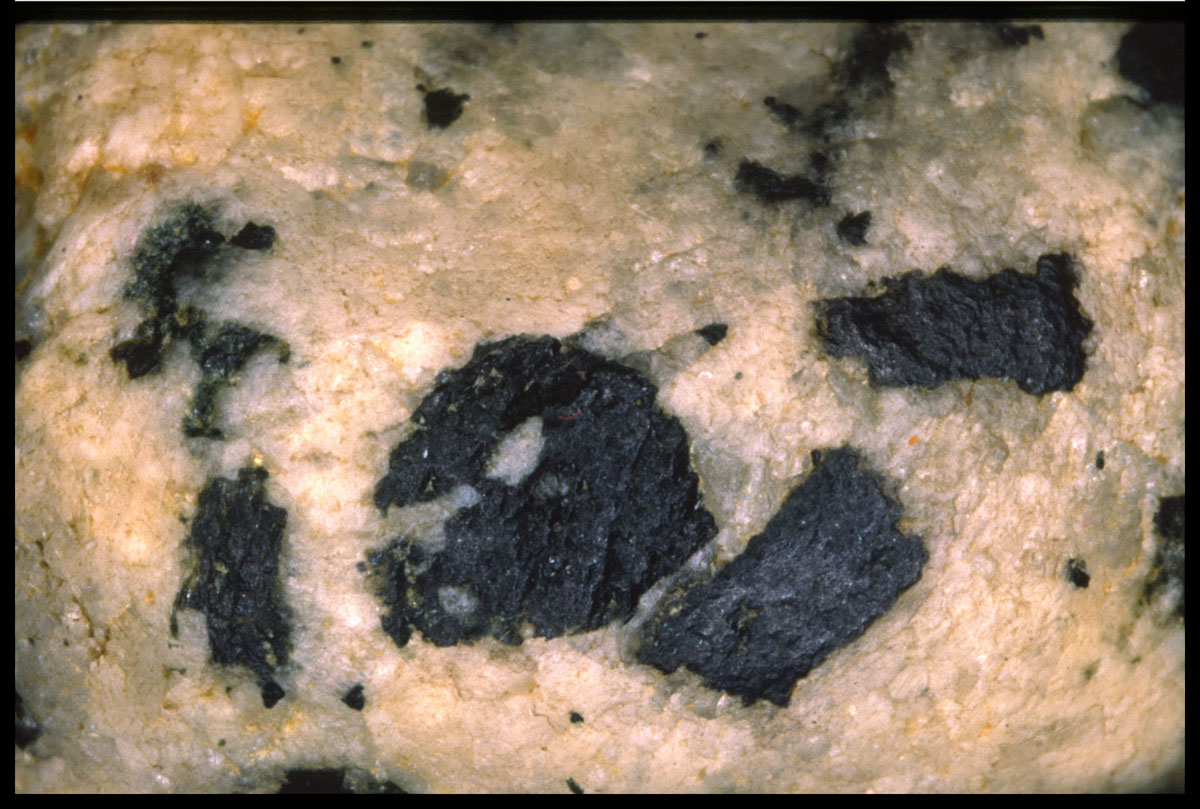

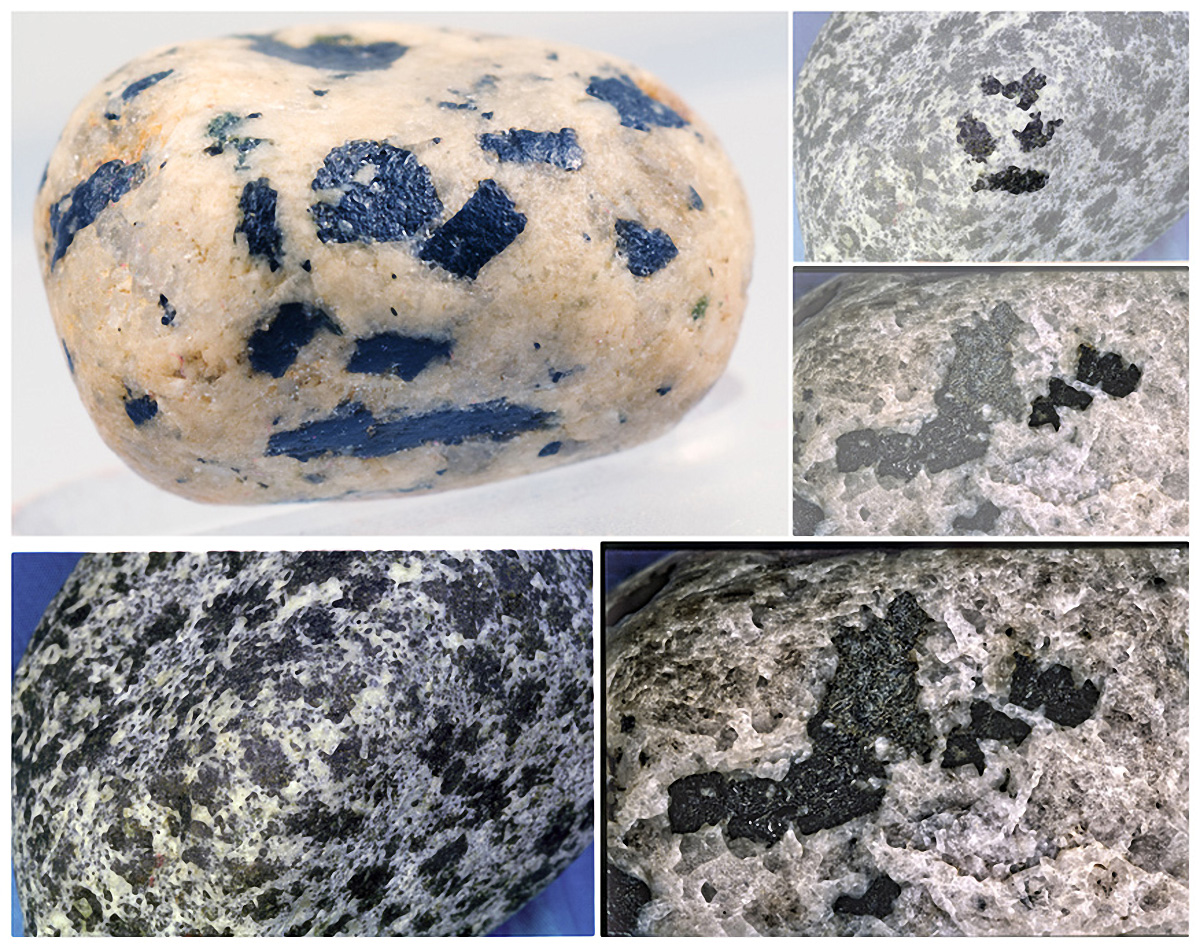

To clarify exactly what we are talking about here, and why it is so important to any study of anametric image writing: immanence is a temporal characteristic which describes that state of fusion in which the components of any concept are united. In this, we are brought back to Bergson's observations regarding the nature of duration as a non-numerical (anametric) multiplicity — a conceptual position consistent with Derrida's description of writing as grammatological in nature, and Tsao's findings regarding the role played by differential contrasts in facial recognition. One way to think about this is in terms of “event”: the sense of connectivity that unites disparate things regardless of their physical distance or sequential separation. For instance, to use an earlier example: each eye in the face of the Three Feather Chief is a differential image element that presents ‘something other in the place of’ each eye; but at the same time, each differential element is fused with — is immanent to — the eye from which it takes its position. At the same time, each image element is united with the other through positionally sharing the location of an eye within an identifiable face: the man with the upraised knife is connected to the mammoth, in that either is in a state of immanence with the position of the eyes they replace — placing both in a state of immanence with each other. The image elements serve as diagrammatic features, and are related to each other in sharing a plane of immanence: that is, the features can be grouped together as immanent to each other; and, such grouping is characterized (as are the fused components of any concept) by the infinite speed with which they appear together, as inseparably fused. When you think of any conceptual structure, you think of it all at once (in a survey of components that proceeds at infinite speed) regardless of how many components it might have; and in this way, the distinct image areas of the Three Feathers become fused into a signature motif which encompasses them all in one instant.

Such a state of immanence is the nature of the grouping patterns that differential image elements form as conceptual structures, analogous to the way in which the phonetic components of any word are fused together within the mind by the word’s meaning. But instead of semiological meaning based upon representational correspondence, such as characterizes phonetic writing, we are dealing with a grammatological functionality that composes grouping patterns from image elements — thereby directly constituting the formation of conceptual structures. In this, we already have much of what we need to begin understanding information conveyed through this form of image writing — information we can become party to across tens of thousands of years, and between linguistic groups that share no phonetic heritage in common. The commonality of those neural processes which inform our conscious awareness of vision can provide the necessary grammatological context which allows this form of image writing to function, in the absence of the shared linguistic heritages that phonetic writing demands in order to convey meaning.

In short: anametric image writing can convey ideas directly, as conceptual structures, without needing recourse to any shared linguistic heritage. Such determinations will prove pivotal for our understanding of how this form of image writing functions.

Defining Point-Of-View

We are still missing a step here, though: when Deleuze and Guattari mention that "Conceptual personae constitute points of view according to which each plane finds itself filled with concepts of the same group", we are brought tantalizingly close to the relationship holding between conceptual personae and positional localization, in terms of point-of-view. This is no minor step, as it would again place us firmly upon the ground of a philosophy which affords us the opportunity to view grouping patterns positionally, in terms of deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Through such a position, we might hope to also draw together the third term of Peirce’s idea of a triadic semiology, with the pivotal position played by personal identification which Schmandt-Besserat outlines in her assessment of phonetic writing’s development in the Near East; from there, we could then combine the two together under the rubric of conceptual personae as defined by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

One particularly productive way forward within this context of personal identity is through reference to considerations explored by the 17th century German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. I will introduce here a lengthy passage by Gille Deleuze concerning ideas developed by Leibniz, because these ideas coincide with areas we are considering here — and they were developed to an incredible degree of logical consistency. To begin, we can note that Leibniz had a very particular notion concerning how each individual was constituted precisely by their point-of-view; and while we may not wish to assert such a position with reference to our own current beliefs, it is undeniable that this approach precisely expresses how we need to proceed when attempting to reconstitute conceptual personae capable of characterizing relationships between people from long ago and the world which once surrounded them, simply through reading examples of the image writing that they left behind:

"Each one, each subject, for each individual notion, each notion of subject has to encompass this totality of the world, express this total world, but from a certain point of view. And there begins a perspectivist philosophy. And it's not inconsiderable. You will tell me: what is more banal than the expression "a point of view"?

“To create a theory of point of view, what does that imply? Could that be done at any time at all? Is it by chance that it's Leibniz who created the first great theory at a particular moment? At the moment in which the same Leibniz created a particularly fruitful chapter in geometry, called projective geometry. Is it by chance that it's out of an era in which are elaborated, in architecture as in painting, all sorts of techniques of perspective? We retain simply these two domains that symbolize that: architecture-painting and perspective in painting on one hand, and on the other hand, projective geometry. Understand what Leibniz wants to develop from them. He is going to say that each individual notion expresses the totality of the world, yes, but from a certain point of view.”

“What does that mean? Of so little import is it, banally, pre-philosophically, that it is henceforth as equally impossible for him to stop. That commits him to showing that what constitutes the individual notion as individual is point of view. And that therefore point of view is deeper that whosoever places himself there.”

“. . . What makes me = me is a point of view on the world. Leibniz cannot stop. He has to go all the way to a theory of point of view such that the subject is constituted by the point of view and not the point of view constituted by the subject. Fully into the nineteenth century, when Henry James renews the techniques of the novel through a perspectivism, through a mobilization of points of view, there too in James's works, it's not points of view that are explained by the subjects, it's the opposite, subjects that are explained through points of view. An analysis of points of view as sufficient reason of subjects, that's the sufficient reason of the subject. The individual notion is the point of view under which the individual expresses the world. It's beautiful and it's even poetic. James has sufficient techniques in order for there to be no subject; what becomes one subject or another is the one who is determined to be in a particular point of view. It's the point of view that explains the subject and not the opposite.”

“The analysis of points of view in mathematics -- and it's again Leibniz who caused this chapter of mathematics to make considerable progress under the name of analysis situs --, and it is evident that it is connected to projective geometry. There is a kind of essentiality, of objectity of the subject, and the objectity is the point of view. Concretely were everyone to express the world in his own point of view, what does that mean? Leibniz did not retreat from the strangest concepts. I can no longer say "from his own point of view." If I said "from his own point of view," I would make the point of view depend on a preceding subject, but it's the opposite. But what determines this point of view? Leibniz: understand, each of us expresses the totality of the world, only he expresses it in an obscure and confused way. Obscurely and confused means what in Leibniz's vocabulary? That means that the totality of the world is really in the individual, but in the form of minute perception. Minute perceptions. Is it by chance that Leibniz is one of the inventors of differential calculus? These are infinitely tiny perceptions, in other words, unconscious perceptions. I express everyone, but obscurely, confusedly, like a clamor.”

“Later we will see why this is linked to differential calculus, but notice that the minute perceptions of the unconscious are like differentials of consciousness, it's minute perceptions without consciousness. For conscious perceptions, Leibniz uses another word: apperception. Apperception, to perceive , is conscious perception, and minute perception is the differential of consciousness which is not given in consciousness. All individuals express the totality of the world obscurely and confusedly. So what distinguishes a point of view from another point of view? On the other hand, there is a small portion of the world that I express clearly and distinctly, and each subject, each individual has his/her own portion, but in what sense? In this very precise sense that this portion of the world that I express clearly and distinctly, all other subjects express it as well, but confusedly and obscurely.”

“What is it that determines the point of view? It's the proportion of the region of the world expressed clearly and distinctly by an individual in relation to the totality of the world expressed obscurely and confusedly. That's what point of view is.”

“Each individual notion has its point of view, that is from this point of view, it extracts from the aggregate of the world that it expresses a determined portion of clear and distinct expression. Given two individuals, you have two cases: either their zones do not communicate in the least, and create no symbols with one another -- there aren't merely direct communications, one can conceive of there being analogies -- and in that moment, they have nothing to say to each other; or it's like two circles that overlap: there is a little common zone, there we can do something together. Leibniz thus can say quite forcefully that no two individual substances have the same point of view or exactly the same clear and distinct zone of expression. And finally, Leibniz's stroke of genius: what will define the clear and distinct zone of expression that I have? I express the totality of the world, but I only express clearly and distinctly a reduced portion of it, a finite portion. What I express clearly and distinctly, Leibniz tells us, is what relates to my body. We will see what this body means, but what I express clearly and distinctly is that which affects my body.”

“OK, there are different points of view. These points of view preexist the subject who is placed there, good. In this event, the secret of point of view is mathematical, geometrical, and not psychological. It's at the least psycho-geometrical. Leibniz is a man of notions, not a man of psychology. But everything urges me to say that the city exists outside points of view. But in my story of expressed world, in the way we started off, the world has no existence outside the point of view that expresses it; the world does not exist in itself. The world is uniquely the common expressed of all individual substances, but the expressed does not exist outside that which expresses it. The world does not exist in itself, the world is uniquely the expressed. The entire world is contained in each individual notion, but it exists only in this inclusion. It has no existence outside. It's in this sense that Leibniz will be, and not incorrectly, on the side of the idealists: there is no world in itself, the world exists only in the individual substances that express it. It's the common expressed of all individual substances. It's the expressed of all individual substances, but the expressed does not exist outside the substances that express it.”

[From: Charles J. Stivale's translation, of Richard Pinhas' transcription, of Gilles Deleuze's lecture series on Leibniz: Lecture One, 15/04/1980]."

Let’s see where these ideas take us, step by step; and let’s start by considering this statement made by Deleuze regarding Leibniz:

“The entire world is contained in each individual notion, but it exists only in this inclusion . . . there is no world in itself, the world exists only in the individual substances that express it. It's the common expressed of all individual substances. It's the expressed of all individual substances, but the expressed does not exist outside the substances that express it.”

At first glance, this approach seems to take us as far away from a scientific perspective as is possible, placing us instead in a realm where imagination alone holds sway. However, in truth, we must admit that in approaching examples of anametric image writing, we are beginning from a position in which we have no direct, empirical access to that world where and when these examples of image writing were created. Further, as far as truth is concerned within the sciences: only that which can be conclusively demonstrated — utilizing procedures which are repeatable by anyone — can be readily considered as fact proven beyond conjecture. What sense, then, does Leibniz leave us with here when confronted by a world we must say does not exist in itself? Precisely: we have the points-of-view held by those who produced examples of anametric image writing; we have those points-of-view that defined these writers of images, which determine them through the expression of those aspects of their world that they perceived clearly and distinctly. We can also say that any such aspects, in being perceived clearly and distinctly, formed within the conscious awareness of these individuals; and that these aspects formed from differentials of minute perceptions, as held relative to their world — which is to say, what we now would call the differential aspects of those non-conscious processes that constitutive (in the particular case we are interested in) the neurology of vision. We have access to the nature of 'minute perceptions', in the context of visual imagery, through clinical studies of the visual neurology shared by all people.

We can say something else as well, invoking insights afforded to us by Félix Guattari: whether or not we have access to the nature of those who produced anametric image writing, such that we can view each through Leibniz’s idea of “substance”, we can approach the creation of image writing examples as a process of “substantiation”; and in this, through the context of the production of stone tools, we are again engaging with processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization — relative to the surface of a mediating substrate for anametric image writing, yes, but still within a visual context.

Already, we are on solid footing here: it is logically consistent to say that a world now lost to us can be reconstituted, by way of relationships holding between what was expressed clearly and distinctly of that world, and, the non-conscious processes of visual neurology — which we necessarily share with those people from so long ago. We have already seen that such a perspectival position, produced through point-of-view as the individuality of personal identity, is indissolubly implicated in the creation of writing — and that this is true both of phonetic writing in the Near East, and image writing in North America. With regard to image writing, we saw how the semiological nature of differential image elements emerged with respect to personal identity, and did so precisely from those non-conscious processes through which facial recognition proceeds; and further, that the neurology of facial recognition functions by processing a multiplicity of differential contrasts — such as would constitute what Leibniz termed ‘minute perceptions’.

The direct implication here is that, starting from an understanding of the non-conscious processes that constitute our visual neurology, and proceeding through these processes by way of images that are composed clearly and distinctly, we can reconstruct the perspectival point-of-view once held by someone who produced image writing — and in doing so, we can have access to the nature of that world which they perceived clearly and distinctly. We can do this because we share with them the same non-conscious neural processes through which clear and distinct perceptions of their world were formed. From this starting position, we can then proceed to ascertain distinctly conceptual structures within image writing, simply by considering the grouping patterns formed from clearly and distinctly demarcated image elements. In effect, we are at this point working within what Deleuze and Guattari termed “geophilosophy”: the implication of conceptual personae in grouping patterns established through a recourse to immanence, as established by acts of deterritorialization and reterritorialization with respect to the world.

Although we do not have direct access to the world in which those who wrote using anametric image writing lived, we can discern ways in which the differential image elements they created group together as immanent with each other in composing conceptual structures. Again, we can discern something of these grouping patterns through clinical studies which document the non-conscious neural processes that inform vision in producing our visual sense of conscious awareness. This allows us to gain a sense of how these people from long ago placed themselves in relation to the world which surrounded them — even though we do not have direct access to the nature of how that world existed for people so long ago. What we can do is infer how the world in which these people lived was formative for their point-of-view; and in this, we can prescribe the relationships holding with that surrounding world, in terms of conceptual personae that are predicated upon functional interconnections between non-conscious neural processes and conscious awareness — connectivities that we can discern, determine, and define to then infer the nature of that world, from the lived experiences inscribed within anametric image writing.

What we are describing here is, in generalized terms, something encountered earlier with respect to the way in which differential image elements acquire a semiological character; what we are consistently finding as a defining factor in all of these considerations, is, “positional localization”. Given that the semiological nature of differential image elements seems to come from positional localization; and that this suggests the establishment of positional localization somehow precedes, and is possibly a requisite for, the semiological functioning of such differential image elements; and considering further, that positional localization is directly implicated in the formation of the grouping patterns found to be holding between diagrammatic features, as facilitated by non-conscious processes: throughout the various functional processes that facilitate the use of images as fundamental elements capable of forming a system of writing, we find that positional localization provides a principle of relational consistency — through a geophilosophy forming within a world which conceptual personae deterritorialize and reterritorialize, to a world which provides the points-of-view that determine the perspectival nature of conceptual personae. Positional localization appears in Derrida’s conception of a writing that is primarily grammatological in nature; positional localization supports the differential contrasts that Doris Tsao has shown determine facial recognition.

Positional localization, as a process, necessarily also occurs in differentials of perspectivism that present shifts in the plane of immanence, and so define variations in a point-of-view — that is, what comes into and moves out of clear and distinct awareness, and in doing so sets a differential context for the minute perceptions that come to define grouping patterns, derived as they are from sensory thresholds of resolution.

Grouping patterns shift through changes in point-of-view; and in doing so, correspond to changes in the immanences that determine the differential nature of minute perceptions. This is another manifestation of positional localization; and it is one which reminds us that, it isn’t just any simple or singular perspective, that ends up defining a point-of-view, which determines the nature of the world embraced by the viewer; it is also shifts in perspective, differentials of perspective, disjunctions of perspective — in short, deterritorializations and reterritorializations relative to the world that in turn create differential shifts in point-of-view — that define the conceptual personae through which we gain a sense of the information conveyed through anametric image writing.

Placing People In Perspective

To conceptualize positional localization in terms of Leibniz’s perspectival point-of-view, we can refer to projective geometry to see how the way in which the world is oriented or configured relative to the viewer is the primary factor determining the the nature of positional localization, as defining point-of-view:

“The summit of a cone is a point of view because, according to projective geometry, it "is the condition under which we apprehend the group of varied forms or the series of curves", for example the circle, ellipse, parabola and hyperbole, that are derivable from one another by projection and section. It is in this way that a continuity has been constructed by means of the projective properties of the conic sections, and it is this very continuity that Deleuze maps onto the variable curvature represented by the point of inflection to determine the point of view of a monad [Duffy, Deleuze, Leibniz and Projective Geometry in the Fold, pg. 141].”

Let’s recall for a moment what Quiroga stated, in the context of facial recognition:

“Another more thrilling possibility is that the exquisite structure of the hippocampal formation—and particularly, the recurrent connectivity in area CA3—gives rise to a major change in the metric space and that such change provides in turn the substrate of two different, though intrinsically related, functions: perception and memory [Quiroga, How Do We Recognize a Face? pg. 976]”.

Very recent insights into the relationships holding between perception and memory now indicate that both are processed by the same sets of neurology — and that, to avoid confusing the two, perceptions are rotated by that neurology to become distinct as memories:

“The transformation of sensory information into a memory was facilitated by a combination of ‘stable’ neurons, which maintained their selectivity over time, and ‘switching’ neurons, which inverted their selectivity over time. Together, these neural responses rotated the population representation, transforming sensory inputs into memory. Theoretical modeling showed that this rotational dynamic is an efficient mechanism for generating orthogonal representations, thereby protecting memories from sensory interference [Libby, Buschman; Rotational dynamics reduce interference between sensory and memory representations, pg. 1].”

Such rotation is essentially definitional of what projective geometry is considered to be; and in this specific instance, that would in turn define the point-of-view for an individual as being relational between perception and memory — which is a perfectly reasonable expression of what makes each person’s identity different from any other. Contextualizing this particular manifestation of projective geometry to Leibniz, we would simply observe that the relationship between minute perceptions and apperception — that is, non-conscious neural processes and conscious awareness — will be the same for both perception and memory, with the stipulation that each instance is in fact a neural rotation of the other. Grouped together as “substance” by Leibniz, we can in turn consider the productive manifestation of these processes within anametric image writing in terms of “substantiation”.

Considering the potential importance of these insights, let’s see what kind of position we can circumscribe through a meta-critique of the material under discussion here, and in doing so examine the formation of conceptual personae as the positional localization of personal identity in point-of-view.

In effect, conceptual personae function as the constructive principles that inform specific relationships with the world. We know conceptual personae by the way in which they make apparent their relationships with the world, as evidenced by the processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization through which they assert their relationships with the world. In this, we must say that the world serves as the motivational factor which induces processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization — which in turn are characterized by the nature of the conceptual personae involved. As Deleuze and Guattari noted of geophilosophy, deterritorialization and reterritorialization revolve around each other, with neither claiming precedence over the other; similarly, we must say that conceptual personae and point-of-view presuppose each other, with neither appearing to the exclusion of the other.

We can discern information about these processes of territorialization, through the grouping patterns we find composing examples of anametric image writing.

We can establish a relationship between these grouping patterns and conceptual personae, through the perspectivism that defines each individual in terms of their point-of-view; and this in turn we can determine in terms of relationships holding between minute perceptions and apperceptions.

We can determine, from those aspects of the neurology of vision that constitute non-conscious processes, the functional nature of these minute perceptions; and we can determine the apperceptive nature of the conceptual personae in question, through reference to the relationships holding between perception and memory — relationships motivated by minute perceptions, which constitute the resolution thresholds that are encountered when mediating substrates are being assessed during their use in the production of anametric image writing examples — relationships that are incised onto the material substrates utilized for anametric image writing, through processes of substantiation.

We do not have direct access to the world which the people who created anametric image writing inhabited; but we can inferentially determine relationships they had with that world, through examining the grouping patterns of differential image elements they incised upon the examples of anametric image writing to which we have access.

Taken all together, then, we find that these considerations define an enviable position — one from which we are well positioned to propose an interpretive methodology capable of constructing a decidedly scientific approach toward linguistics (at least within the context which we are presently working).

Admittedly, we are working to reconstruct a world which no longer exists; but in engaging with such a perspectivism as Leibniz proposed, we are not at a loss as to how we might proceed. In finding that the world(s) we would reconstruct can be expressed through relationships holding between ‘minute perceptions’ (as non-conscious processes) and ‘apperception’ (as conscious awareness); and that, in the context of those neural processes which constitute vision, this is territory that is well documented by modern clinical studies, we must realize that there is no lack of accurate guidance to be found here.

In constituting the perspectival point-of-view which Leibniz outlines, we further find ourselves defining a position which Charles Sanders Peirce proposed as being integral to any assessment of linguistic function: that of an interpreter, who connects any semiological element with that which it ‘stands in the place of’. We have a more refined approach for determining such “standing in place” than Peirce had access to, for we can invoke the relationships holding between non-conscious processes and conscious perception here; and we can also draw upon such philosophic insights as are afforded by the work of Deleuze and Guattari. Through their explorations in post-structural philosophy, we can develop, refine and extend our understanding of the conceptual relationships established within anametric image writing, through a thorough assessment of those grouping patterns that are actively constituted from states of immanence, as they are instituted by the non-conscious neural processes which inform vision.

In Summary

We can determine specific processes of territorialization and deterritorialization which define relationships held by those conceptual personae who created the examples of anametric image writing we are now in a position to study; and in doing so, we are recreating (through perspectivism) aspects of the points-of-view from which these examples were created. In all of this, we have found an alternative to the shared, learned phonetic heritages that singularly inform meaning for distinct linguistic communities — and we have done so by way of our access to neural processes that have been scientifically documented and clinically demonstrated to be shared by all humans.

We can employ the phenomenological ‘conditions through which visual consciousness appears’ to reconstitute the conceptual structures that informed these examples of image writing; and we can do so by employing, in place of the phonetic meanings that inform speech, neurologically functional determinations that define vision.

Here, we can at least in part realize one of the goals of post-structural philosophy: creating a truly scientific approach to linguistics. In this, we are advancing toward an understanding of how empirical evidence, as direct experience of the world (implicating epistemological considerations regarding the conditions under which truth can be ascribed), can be formulated in such a way as to allow accurate information about experiences to be coherently transferred to others (demanding metaphysical determinations concerning theory construction), in the form of what Sartre referred to as “non-subjective transcendental fields” (of knowledge):

“What is a transcendental field? It can be distinguished from experience in that it doesn’t refer to an object or belong to a subject (empirical representation). It appears therefore as a pure stream of a-subjective consciousness, a prereflexive impersonal consciousness, a qualitative duration of consciousness without a self. It may seem curious that the transcendental be defined by such immediate givens: we will speak of a transcendental empiricism in contrast to everything that makes up the world of the subject and the object. There is something wild and powerful in this transcendental empiricism that is of course not the element of sensation (simple empiricism), for sensation is only a break within the flow of absolute consciousness. It is, rather, however close two sensations may be, a passage from one to the other as becoming, as increase or decrease in power (virtual quantity) [Deleuze, Pure Immanence, pg. 25].”

Writing constitutes a non-subjective transcendental field — as does any coherent way of systematically organizing knowledge so that it can be transferred or otherwise communicated beyond the direct experiences in which it arises. Conceptual personae are not subjectivities; point-of-view is not a subjective position when it is defined through perspective. Similarly, geometry is a non-subjective transcendental field precisely because its axioms do not rely upon any specific observer in order for them to be consistent, and true; and we can similarly construe an understanding of anametric image writing as such a non-subjective transcendental field, insofar as we are able to localize its functional nature within “a prereflexive impersonal consciousness” (such as is constituted by non-conscious neural processes, or “minute perceptions”) immersed within a world wherein deterritorializations and reterritorializations of conscious temporal interaction occur.

In effect, this Three Feathers motif served as a ‘signature’ of sorts which is identifying a distinct, historical individual.

In effect, this Three Feathers motif served as a ‘signature’ of sorts which is identifying a distinct, historical individual.