Introduction

There is no denying the major role writing has played in human culture. By definition, history itself is directly linked to writing: those places and times where humans lived prior to the invention of writing are defined as being “prehistoric”; and indeed, people who lived without a written culture are themselves considered “prehistoric”. When it comes to how we visualize civilization itself, much hinges upon the presence (or absence) of writing.

The kind of writing you are reading right now has a very specific origin, which is quite well documented. Generally, when people think about how phonetic writing — which shows the sounds of speech through symbols — evolved, they look to an origin in the Near East. Other forms of writing evolved elsewhere; but where those forms of writing started, and how they developed, has not been clearly discerned or well documented to date. As a result of the extensive documentation outlining its origin, one particular form of writing — phonetic writing, such as is written using an alphabet — is generally accepted as being representative for any and all forms of writing.

This is in fact neither necessarily, nor actually, so; and, there are serious implications that follow from assuming it to be the case.

Nevertheless: even though the development of phonetic writing does not establish a model which all systems of writing must necessarily follow ‘to the letter’; the documentation that has been established, in outlining how such a system of writing evolved, can provide indications of various developmental stages that might also be important in the evolution of other writing systems.

Overview

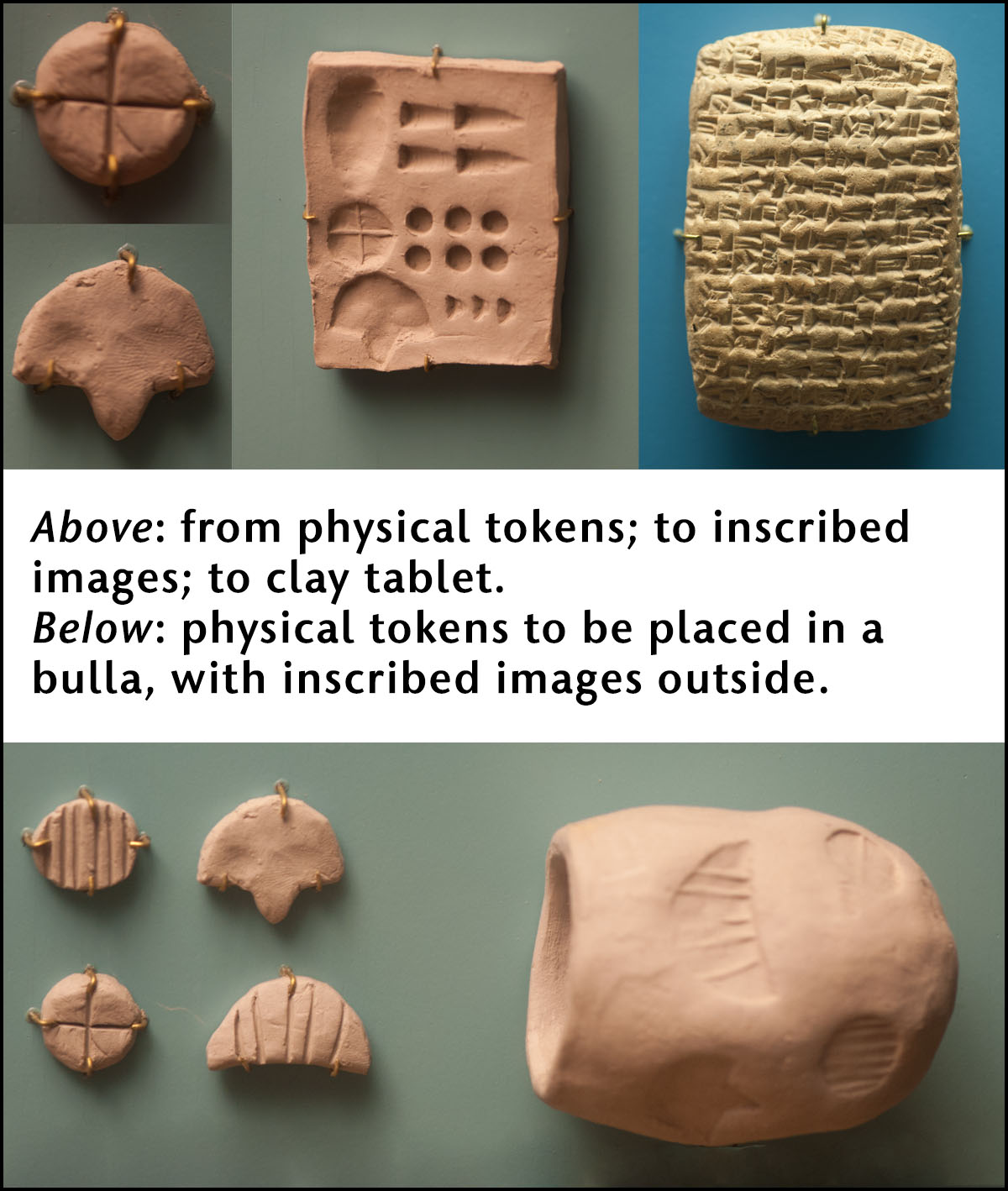

The developmental path of the most widely known form of writing (phonetic) has been extensively documented. One researcher who has been particularly incisive in her analysis of this is Denise Schmandt-Besserat. Her exceptionally detailed examination of how writing evolved in the Near East meticulously traces this path: from its representational beginnings in what was basically a system of accounting (where clay tokens paralleled the place taken by physical goods during trade); to the clay envelopes that held groups of tokens, with the outlines of those tokens pressed into the still-wet clay of the envelope before it was sealed; to the clay tablets that replaced these tokens, with characteristic markings instead incised onto these flat surfaces; to groups of symbols being used for the names of people — which led to the establishment of phonetic writing, where symbols represented sounds rather than physical goods that were being 'held to account' in trade.

Schmandt-Besserat notes, however, that other systems of writing which did not develop from this Near Eastern point of origin have not been well documented as to how they came into being:

“Writing is humankind's principal technology for collecting, manipulating, storing, retrieving, communicating and disseminating information. Writing may have been invented independently three times in different parts of the world: in the Near East, China and Mesoamerica. In what concerns this last script, it is still obscure how symbols and glyphs used by the Olmecs, whose culture flourished along the Gulf of Mexico ca 600 to 500 BC, reappeared in the classical Maya art and writing of 250-900 AD as well as in other Mesoamerican cultures (Marcus 1992). The earliest Chinese inscriptions, dated to the Shang Dynasty, c. 1400–1200 BC, consist of oracle texts engraved on animal bones and turtle shells (Bagley 2004). The highly abstract and standardized signs suggest prior developments, which are presently undocumented.

"Of these three writing systems, therefore, only the earliest, the Mesopotamian cuneiform script, invented in Sumer, present-day Iraq, c. 3200 BC, can be traced without any discontinuity over a period of 10,000 years, from a prehistoric antecedent to the present-day alphabet [Schmandt-Besserat: The Evolution of Writing; pgs. 1–2].”

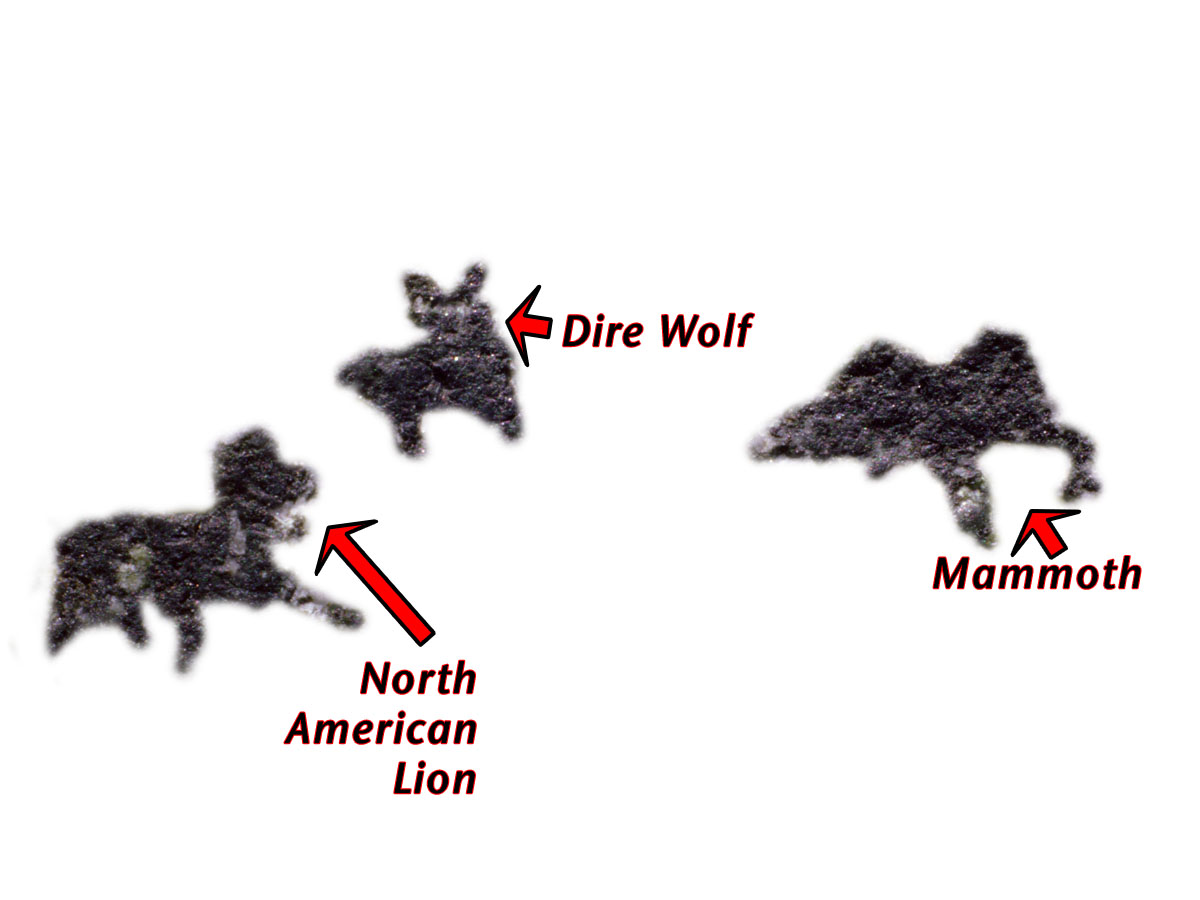

It will be my contention that the glyphic writing systems which emerged in China and Mesoamerica share a common point-of-origin, in the form of that image writing native to North America which I am here documenting.

In any event, many of the stages in the developmental processes Schmandt-Besserat documented (through a process she describes as “cognitive archaeology”), with reference to the evolution of phonetic writing, can be seen to be at least inferentially influential in the development of the other systems of writing she mentions. By way of example, several points of comparison can be discerned through an analysis of the form of image writing I have been documenting. As Schmandt-Besserat stresses:

“Cognitive archaeology makes it clear that the immense value of the token system was to bring mankind, in the course of its millennia long development, to the level of abstraction necessary for literacy and civilization [Schmandt-Besserat: Tokens and Writing: the Cognitive Development; pg. 154].”

Certainly, as with any form of writing, it is possible to discern and document processes of abstraction inherent in the form of image writing I have been studying — and in doing so, to outline significant points of comparison between this form of writing and those forms of phonetic writing which are now used extensively around the world.

Definitions

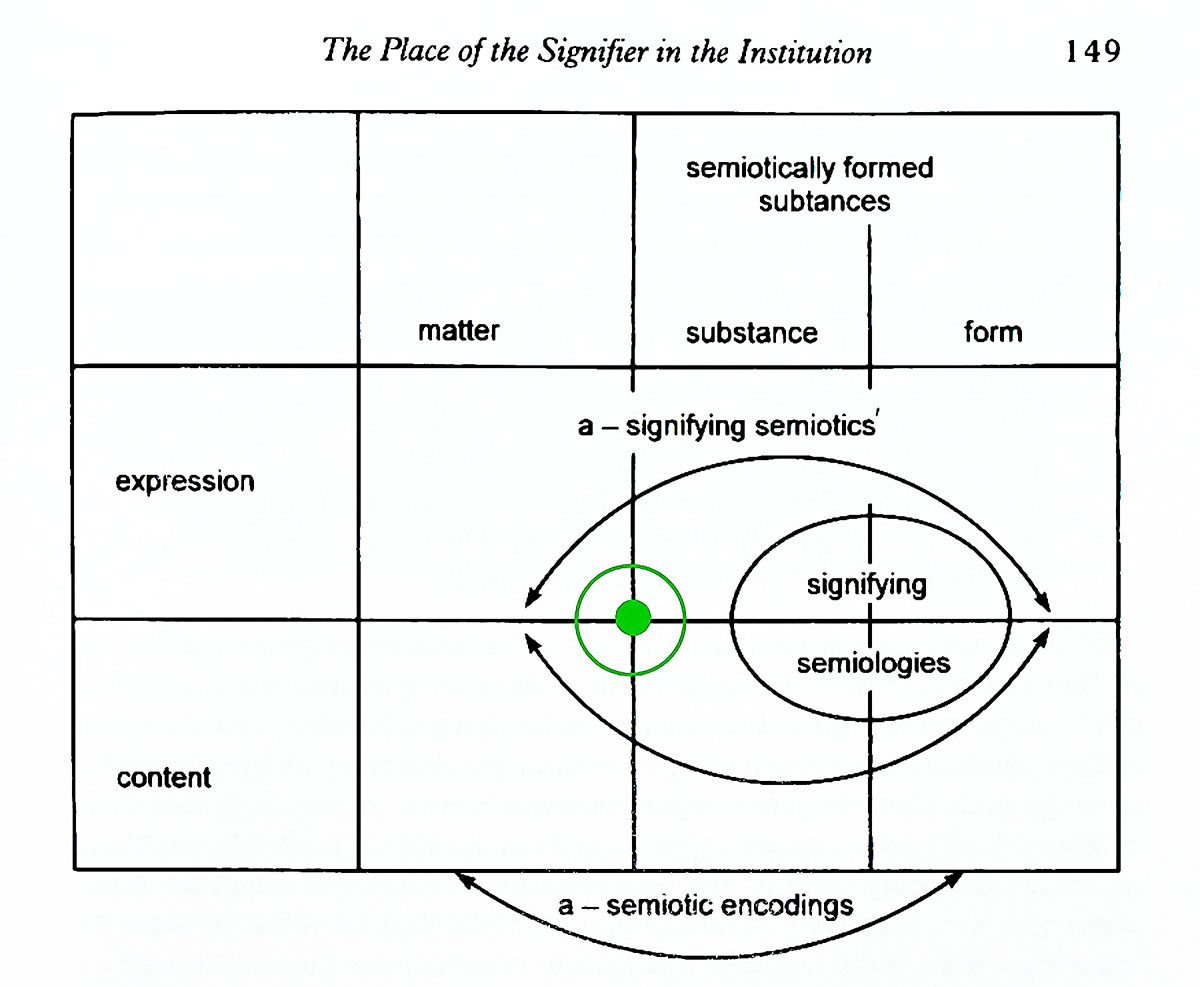

It may come as a surprise to some that the idea of “cognitive archaeology” is not limited to the field of archaeology. As a concept, such an approach is also integral to the field of post-structural philosophy (my area of specialization), as demonstrated by such fundamental texts as Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge. As with other philosophers holding firm ground upon the history of those concepts found within their field, Foucault examined through numerous innovative investigations the ways in which ideas can change over time, as documented through written texts that originated in different time periods. Of course, such an approach can only be applied as far back as we have written texts to consult. Schmandt-Besserat’s work with cognitive archaeology pushes that approach back about as far as it can function with regard to writing, while recognizing that material production itself can be incisively indicative of cognitive development. Indeed, one approach to linguistic analysis pioneered by the practicing psychoanalyst Félix Guattari considers the role that the physical properties of intentionally produced objects can play, in a conceptual context prior to the application of signification within language:

If we are: 1) trying to push our historical grasp of how concepts relevant to this study arise, toward a time before writing actually emerges; and, we are: 2) seeking to find a ground which is based broadly enough to encompass writing-in-general (rather than just one particular kind of writing); then, we need to: 3) find some comparative principle that will allow us to apply an interpretive methodology which is capable of discerning the contrasting differential parameters making each form of writing distinct in its own right. In approaching image writing, our first inclination might be to try and link objects directly with the thoughts they would seem to implicate — much as we naturally link words with objects. This immediately places us upon suspect ground, however, in that we cannot assume our use of language approximates that of any language to which we no longer have access; and similarly, we cannot assume any specific artifact would engage the same subjective responses we might have from within our modern culture.

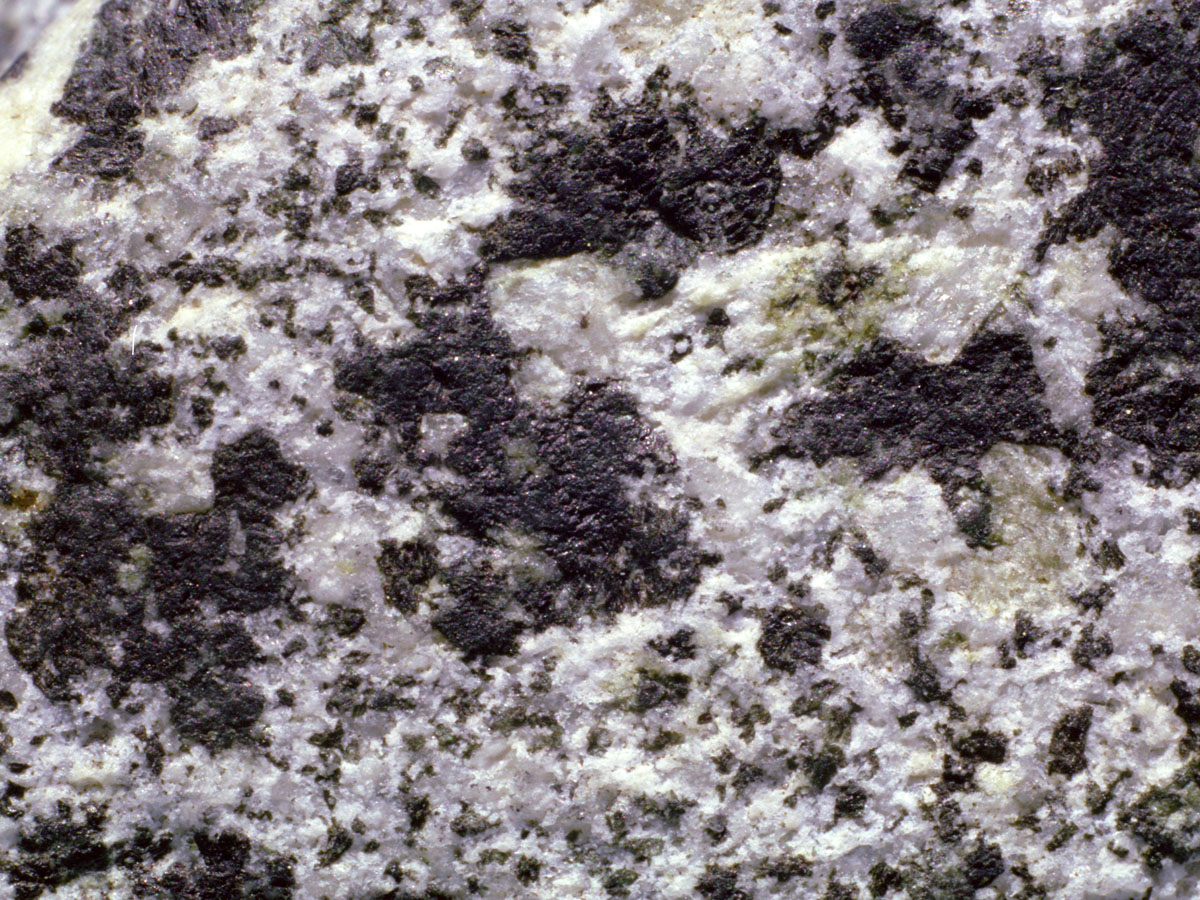

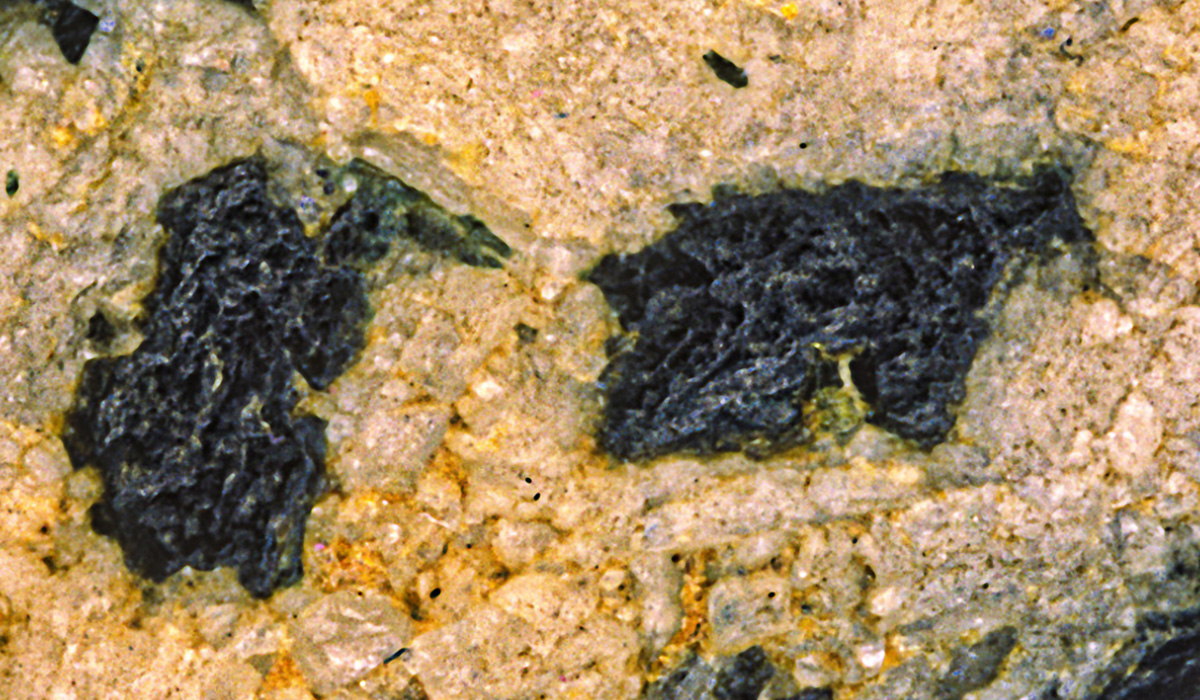

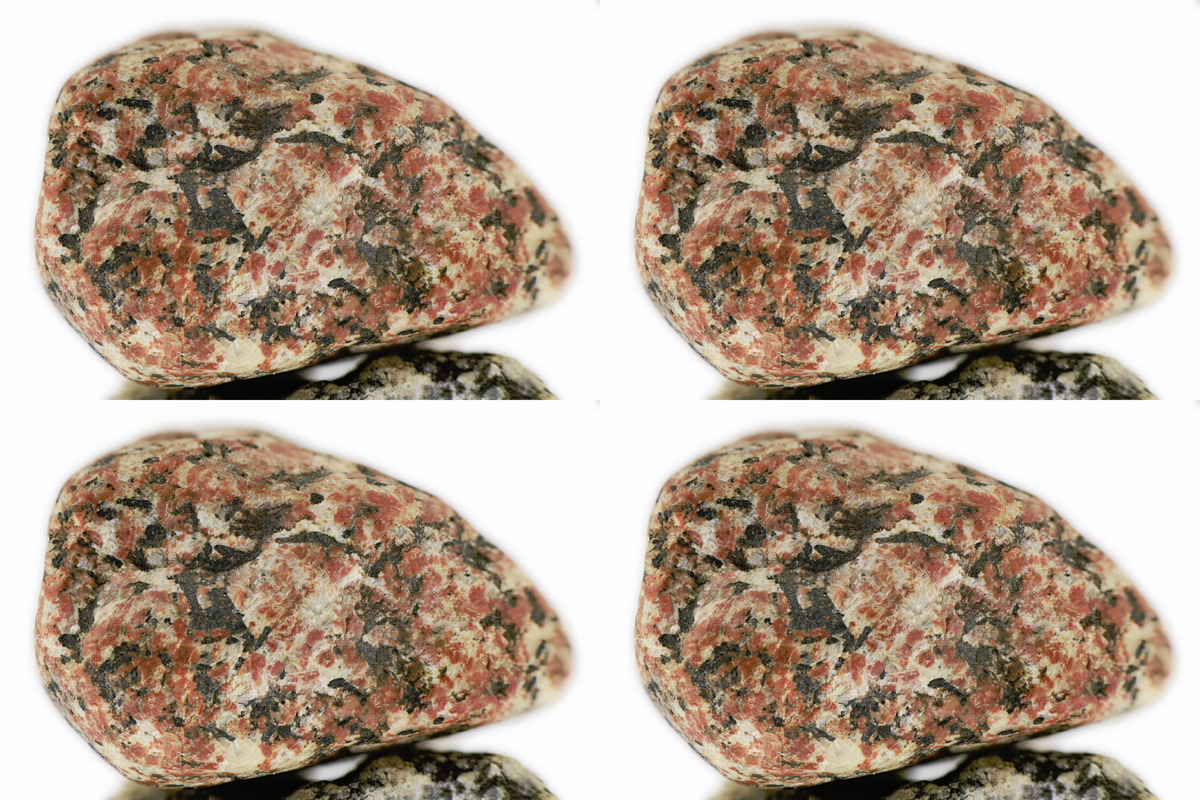

Guattari's approach suggests a different path forward: in considering how those who crafted stone tools viewed their materials at hand, we can immediately see that any initial piece of rock chosen for crafting a tool would at first glance be considered simply “matter”; that is, relatively undifferentiated beyond being physically solid. In the course of crafting a tool, however, the various qualities of the stone would be considered and utilized in creating the tool: the balance, the planes of cleavage, the friability, and so on. It is this process of ascertaining material qualities that constitutes the conceptual shift from considering something as undifferentiated “matter”, to viewing the same material in terms of its substantive qualities — to considering that "matter" as a “substance”.

We can roughly term this process as “substantiation”; and in the context of producing instances of image writing, this term takes on added nuances: as a process which is undertaken in the substantiation of a craftsperson’s memory, as a making manifest of their experience through substantiating the nature of those interactions in the world around themselves which they have witnessed.

Note also that Guattari describes the linguistic functions that are grounded in such interactions as being a-signifying and anasemantic: they are not characterized by meaning, as processes of (phonetic) signification are; rather, they are distinguished by functionalities and, as such, are more conducive to grammatological analysis. This distinction allows us to avoid a major pitfall inherent in phonetic forms of writing, which are rendered indecipherable when the arbitrary meanings that link signifying characters with signified sounds or, signifying words as sound patterns with signified objects of reference, are lost.

When we are dealing with a form of image writing which is a-signifying and anasemantic, we can still seek to discern substantiations that incorporate grammatological functionalities — and in doing so, derive information from the arrangements of image composites we encounter therein.

One viable step toward such an approach, and one that certainly bears consideration, is that of a “geophilosophy”, as outlined by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari:

"Subject and object give a poor approximation of thought. Thinking is neither a line drawn between subject and object nor a revolving of one around the other. Rather, thinking takes place in the relationship of territory and earth . . . The earth is not one element among others but rather brings together all the elements within a single embrace while using one or another of them to deterritorialize territory . . . Territory and earth are two components with two zones of indiscernibility — deterritorialization (from territory to earth) and reterritorialization (from earth to territory). We cannot say which comes first [Deleuze and Guattari, What Is Philosophy?, pgs. 85–86].”

This is simply to say that, examining how objects were used in carving a place out for people within the world will give us a better idea of how people were placing themselves in their world; better, that is, than trying to imagine first how people saw their world, and then attempting to determine how people were placing themselves within the world. Attempting to dictate in a predetermined fashion how people perceived their world, and then placing them within that preconception, is an approach that is ideological in nature — and as such, almost inevitably leads to racist determinations regarding the people being assessed from outside their own culture. People are always already within the world; and in examining how they situated themselves through the objects they used, we get a clearer idea of how they anchored themselves to their world.

Looking at how the things that people made would have allowed them to better live in their world, could give us a clearer idea of what and how these people thought, than would trying to imply relationships directly between those things and the thoughts of the people who made them. How people responded to the different aspects of their world, depending upon where and when they lived, could allow us to better grasp the ideas that informed their decisions. This is an approach much better suited to discerning how people placed themselves relative to actual world conditions, than is assuming we can infer a universality of thought that would allow us to directly compare conceptual developments across regional and cultural divides.

We can't assume at the outset that relationships we infer between people and things tells us about their ways of being in the world; but we can see the physicality of how things were intentionally created, with a functional place in mind relative to the world, as indicating how people approached living within the world where they found themselves. This is a subtle distinction, but one which causes an ever greater difference in interpretive methodologies the farther we find ourselves from the people we are asking about — or the farther different groups might actually be from each other within the world.

Thus in seeking a place to start when comparing: 1) the forms of phonetic writing which arose from, a point-of-origin in the Near East; and, 2) the forms of image writing which are native to North America, we might find some success in considering for each the various relationships apparently holding between territory, and the earth, for either.